What really is 'Chhatra Janata'?

Naveeda Khan

Interruptions

On August 5, 2024, Sheikh Hasina boarded a helicopter with her sister Sheikh Rehana and left Bangladesh as people, urged by students, poured into the streets of Dhaka. General Waker-uz Zaman, the chief of army, demurred in the face of her insistence that the army teach the students a lesson, presided over her resignation, and escorted her onto the helicopter that took her part of the way out of Bangladesh to India. He declared that the army was with the people and urged calm off the jubilant crowd while his men stood aside as people swept through Hasina’s house walking away with fishes from her aquarium, chicken from her coop, even her exercise machine, among many other objects.

An early indication that students were not pleased with this behaviour was that a group of them stood in front of her house, urging those taking off with the ex-PM’s household goods to return their loot. A young woman interviewed said she had been there all day reclaiming the objects. Indeed, there was a large stack of things behind her. She said it’s clear from looking at some of these things that they are personal: It’s not right to simply take them.

That very same day, August 5, General Waker said in a press briefing he had called on members of each political party and respected others to create an advisory government. Dr. Asif Nazrul, the law professor of Dhaka University who had been outspoken in his criticism of Sheikh Hasina’s government’s handling of the student-led quota movement, was among them. He came out of the room in which conversations among the army convened people were in session to assure that everyone was participating in good faith and that he was confident of a good outcome.

Meanwhile, the student leaders of the quota movement announced that they would hold a press conference the evening of August 6, at which they would be revealing the group that would make up the advisory government. There was a clear face off. For a short while I had the sinking feeling that the army would do what it has done on other occasions, here as elsewhere in the world, which is to capture a moment of revolutionary potential. Instead, the Bangladesh army held back from further pronouncements. It presumably also negotiated with the students because at their press conference, in addition to declaring that the 84-year-old Muhammad Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank and Bangladesh’s Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, was to serve as chief advisor, the students named some of the same individuals initially assembled. This advisory government entrusted with leading the country now also included two students, Md Nahid Islam and Asif Mahmud Shojib Bhuiyan, who were key figures in the quota reform movement. Mahfuz Abdullah, considered one of the “theorists” of the student movement, was later appointed a special advisor to Yunus.

For a second time over the course of the first two days of Bangladesh’s newest era the students did something that interrupted the usual flow of events. Just as they stepped in to ebb looting, they stepped in to insert themselves into the formation of government. These acts of interruption are important not only because of the principle in each, “thou shalt not steal,” “thou shalt not steal the people’s will,” but also because each time these acts disrupted the given scripts and created an opening, however small, for something different to emerge. We saw something similar happen when news of attacks on Hindu sites of worship was broadcast in the days following what is now being called “July’er Gono Obbhutthan” or the People’s Uprising of July, with students organising with their allies to stand before temples to protect them.

Once the advisory government was established and publicised, in different interviews, members said, "We are bound to realise the will of the chhatra janata[literally ‘student people’].” This is an interesting phrase, as it can both mean the specific and bound constituency made up of students and can also be taken to imply an isomorphism between students and the people, students as the people or students for the people. In her 2021 Economic and Political Weekly article “Dhaka 1969”, in referring to the earlier moment in Bangladesh’s history, anthropologist Nusrat Sabina Chowdhury also remarks on this curious formulation. However, she treats the phrase as referring to two distinct entities, “students” and “people”, without implying any specific relation between them. But what if we were to speculate, what are students “as” or “for” the people?

In this fourth instalment of my reflections on the summer of 2024 in Bangladesh, I explore this figure of the “student people” and what political acts may come under this category. I am calling it a “politics of practice,” in which small acts and practical responses maybe mere interruptions, but insofar as they break from the familiar, or rather play with the familiar in surprising ways, they have the potential for producing major consequences. I know that it has been several weeks since August 5 or July 36 as some have called it, and that many good and bad events are playing out on the national scene, which call for our most urgent attention. Yet, I maintain that we must delve into the cultural production of this movement from which we are to build an outline of such a politics of practice.

In what follows, I first parse the figure of the “student people” and then study a few of their key artefacts from the reems of posters, videos, photographs, cartoons, memes and graffiti that has come out of this movement. It is my contention that the inter-citational nature of these artefacts of student expression of frustration, the way in which they call to one another, may provide us an angle of entry into how seemingly small gestures have interruptive capacities. Of course, we know that social media is well able to both amplify and broadcast widely for better or for worse. Here, I am less remarking on this double-edged nature of social media and more on media artefacts as part of a politics of practice.

Student people vs student politics

I would say that while there is a historical distinction to students within the context of Bangladesh, there is a further difference between a politics of students as/for people and student politics and global youth politics. That students occupy a particular place of importance within the history of Bangladesh comes through very sharply in the 1987 novel Chilekothar Sepai (The Soldier in the Attic) by Akhtaruzzaman Elias. Coincidentally I was reading this novel alongside the events unfolding in Bangladesh. I found a curious resonance between the fictionalised Dhaka of 1969 and the Dhaka of 2024, with some of the same terms, such as shoirachar or autocrat, in circulation then in condemnation of the Pakistan government of Ayub Khan as now, and of course the same acts of protests, such as, meetings in iconic sites, processions, even the burnings of buildings associated with a despised government.

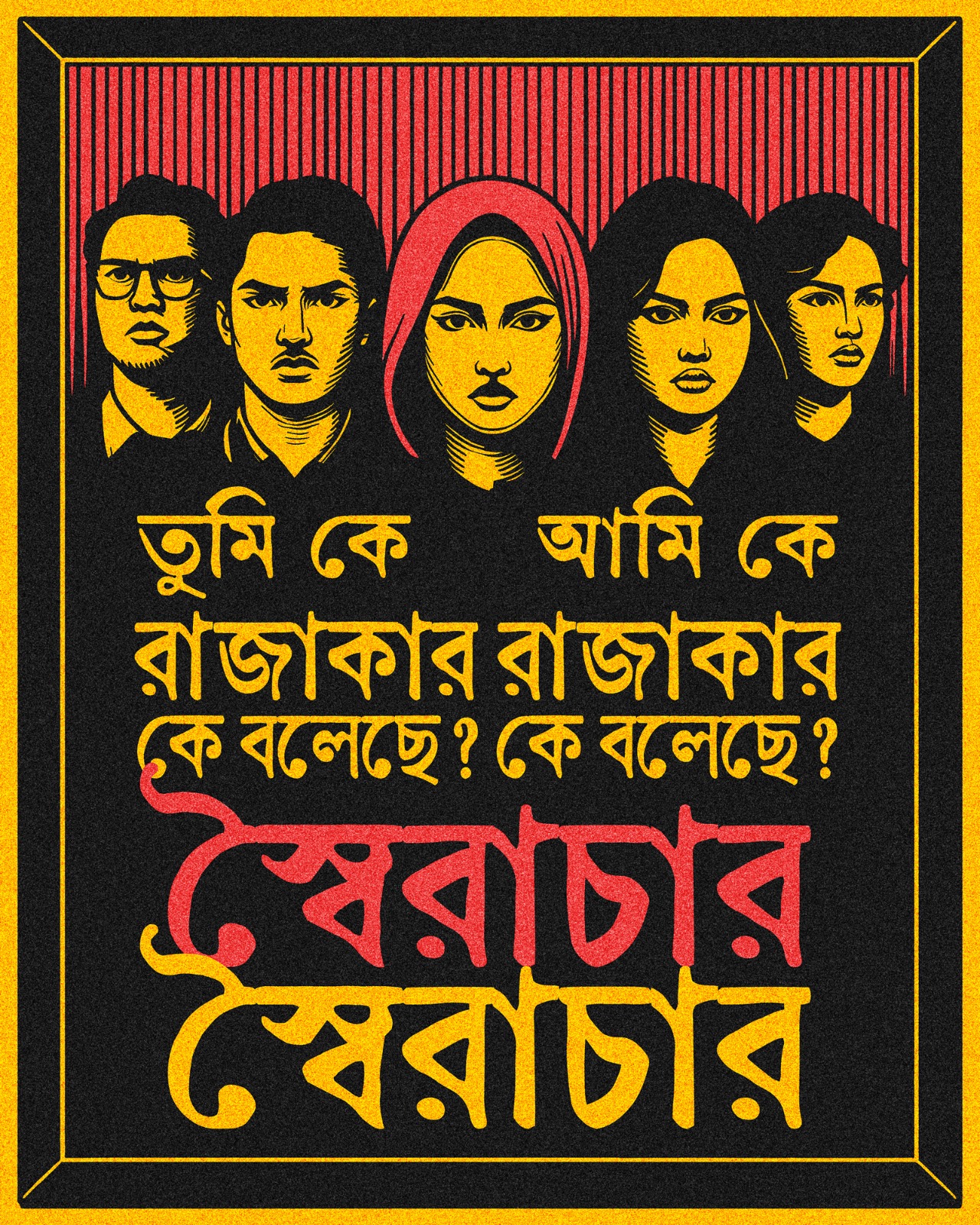

Student leaders in their diversity are everywhere in the novel, from the nationalists who wish a country to be run by its own people, free to make their own mistakes, to the communists who wish a country to be restructured so as not to reproduce previous wrongs. Also noteworthy is the solidarity between students and rickshaw-pullers in the novel, which was also observed in the 2024 movement, in which the pullers were seen standing on their rickshaws to salute the students and risking their lives to transport wounded people and dead bodies from sites of confrontation(Image 1).

Image 1. Photo: Star

That students mean something, if not exactly leadership—as there are others including politicians, union organisers and local businessmen vying for that role within the novel—that they provide moral authority, direction and coaxing is borne out by Haddi Khijir, the erstwhile rickshaw-puller who is one of the novel’s protagonists. Khijir has enough revolutionary fervour to excite and organise a phalanx of rickshaw-pullers, but still dotes on individual students, such as Anwar, and looks out for those he calls “Payjama-Panjabi-Muffler” (referring to students on account of the generic and homespun nature of their clothes) in the crowd to take their lead in the procession.

This modality of being alongside the people, apparent also in the acts of students taking up arms against the Pakistan army in 1971, later streaming into the countryside to offer food and support during famines and floods, is quite distinct from what is called “student politics” in the context of Bangladesh and which the present-day students at the helm of the mass movement now wish to have purged from their institutions. By this they mean the student bodies organised along party lines, such as, the Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL), Awami League’s equivalent within university campuses and halls, Jatiyatabadi Chhatra Dal (JCD) that of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, and Islami Chhatra Shibir of the Jamaat-e-Islami party. These “students,” many of whom are past the age of being students, are entrenched within campuses and halls, and serve as the conduit for the actions and violence occurring at the national stage. Students and faculty who sought to clear out the halls of “student politics” right after the fall of the AL government amassed an impressive arsenal of handguns, machine guns, grenades, dangerous chemicals, and so on from the belongings of such “students.” Among the asks of students of the advisory government, which includes constitutional reform to “interrupt” dynastic rule and prevent one-party rule, is to get student politics out of their educational institutions.

Students as/for people are also distinct from the global youth movements of recent years. I speak briefly of the two that I have followed. Youths have organised extensively around the climate issue at all scales of the problem. In a 2021 paper on youth politics, Faisal Devji points out that the young participating in such organising speak as those who must remind adults of their responsibility to the young and the yet unborn. In other words, they don’t claim adulthood or a fully constituted selfhood but as partial ones needing adults to do their bit for the future. The most recent and compelling youth organising has been around the issue of Gaza and urging the US to prevent genocide. Here, in an interesting difference from the youth-led climate movement, the most common reference is to the past and the need to retell the story of Israel’s foundation as that of settler colonialism.

In contrast to these acts of youth organising, the students in Bangladesh do not see themselves as youth as such. They see themselves as fully constituted adults, bearing responsibilities for others, such as younger siblings or ailing parents, even the people of the country, while trying to get an education to make something of themselves. Maybe the difference between students as/for people and global youth politics is that the students of Bangladesh are largely preoccupied with the present, with making it liveable, starting with making it breathable. As the young student leader Shima Akhter relayed in an August 14 conversation with her on the events of Bangladesh, “We were feeling suffocated; we couldn’t do anything without being violently shut down.” and “You realise our generation has never voted although there have been no fewer than three elections during our lifetimes? We had to do something, anything, even if it meant our own deaths.” The resonance with the “I can’t breathe” slogan of racial justice in the United States is likely unselfconscious, as the Black Lives Matter Movement has not had traction among Bangladeshi students as the issue of Palestine. Furthermore, dom bondho hoye jacchhe and nishyash nite parchhi na have a long provenance in Bengal. But what these articulations suggest is the extent to which a structure of feeling, that of suffocation, has acquired universal salience as a mode of critique of our contemporary condition.

Politics of practice

The iconography, now well associated with the work of Debashish Chakrabarty, was in display almost from the start of the quota movement, as for instance the poster calling out Hasina as the autocrat who calls students traitors/collaborators.

Image 2. Visual: Debashish Chakrabarty

The image is of young men and women, with generic features, stylistically like 19th century Bengali lithography and popular prints, sketched in bold lines and bright colours, with sparse yet telling details, such as a scarf over a head indicating gender and possibly social orientation (conservative, even pious). The figures of the students in the image confront the viewer frontally, seeking to lock eyes with the onlooker. They are also set off from one another to suggest many more behind those we catch sight of but who are not here represented. We are encouraged to imagine a multitude of students but also to take those represented as icons of them. There are many variations of this style, with Chakrabarty encouraging people to borrow his imagery without waiting for his permission, suggesting that while the awareness of intellectual property rights had taken hold, there was a need for contagious imagery in the middle of the movement.

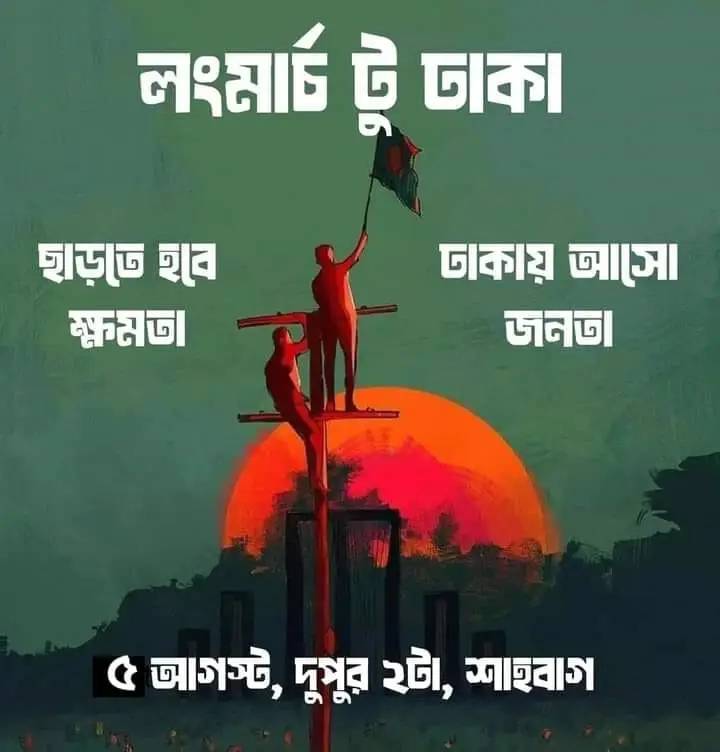

Such iconographic elements are also apparent in posters by other student artists in which a few in the distance hold up a flag as if to wave on crowds about to enter the frame, but which basically home in on a few figures (this is also an artistic rendition of a photograph).

Image 3

Other posters are not averse to representing the multitude of students and the crowds along with them as an undifferentiated swarm.

Image 4. Visual: Shaikh Sultana Jahan Badhon

In a particularly striking image(Image 5), we see a swarm, in the shape of Bangladesh, converge and become one, to drive home not just the fact of unity but unification behind one single call, for Hasina to resign.

Image 5. Visual: Earki

It is doubly poignant that the slogan in the poster—Ashchey falguney amra kintu digun hobo or “Next spring, we will be double”—is the title of a famous book by the Bangladeshi activist and author Zahir Raihan, who disappeared in 1972. I take the word digun or double in the slogan to mean “again” in both the sense of “we will be again,” with an emphasis on being, or “we will be again,” that is, it (the revolution) will happen again and again as necessary, with an emphasis on again.

This stylized interplay between the iconic few/multitude/crowd/swarm in student poster art finds a kind of cathartic release in countless videos posted on YouTube, X, Facebook, and Instagram in which we see individuals standing on structures wave the flags as in the posters, while huge numbers of people gather and move, seemingly spilling over the poster frame. When represented in fast motion, these videos of people gathering and marching give a feeling of a frozen picture, such as that of posters, coming unstuck, finally coming to life. As an aside, it is disheartening that most of the representations of this jubilant crowd on social media, most by international media, portray them negatively as though they are looting and pillaging widely. This inability to see a crowd for both its good and bad aspects suggests either a fear of crowds as such or more specifically majority Muslim crowds, even if Islam isn’t their defining element at these protests, but rather a very justified anger against an autocrat.

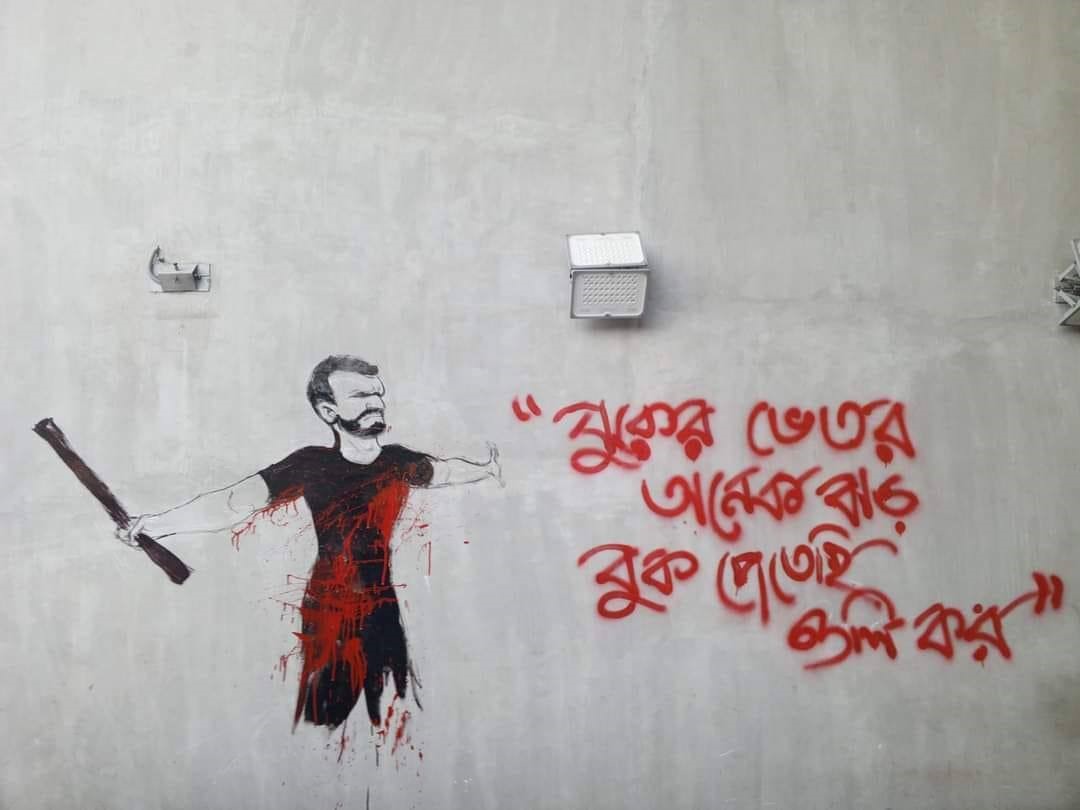

The interplay between the actual and the pictorial also proceeds in the other direction. The photograph of Abu Sayed with his arms outstretched minutes before he is shot and killed is perhaps the most depicted in artistic form and quickly became as much a symbol of state brutality as of heroic resistance(see Image 4 and Image 6).

Image 6

There is another photograph that went viral. It is of a policeman clamping his hand over the mouth of a protesting student.

Image 7. Photo: Collected

This photograph is soon painted profusely, with the paintings not just indexing the event but also symbolising the silencing of voice.

Image 8. Cartoon: Morshed Mishu

As more and more elements are subtracted from the painted image, a hand in the gesture of a clamp is enough to strike fear.

Image 9. Visual: Nayera Noor

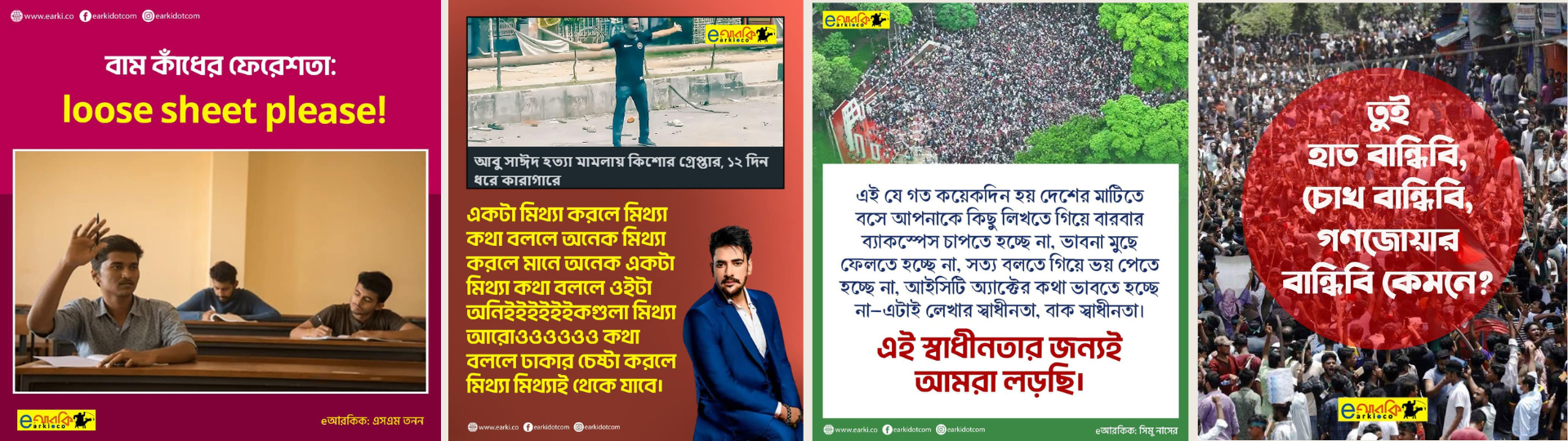

Memes that focalise the hand give expression to heartfelt, fervent beliefs that the right (image 10) and truth (image 11) will prevail and that free and fearless speech is possible (image 12), and, that the tide of humanity will wipe away autocracy (image 13):

Images 10, 11, 12, 13. Credit: Earki

Others made fun of the two sons of the two women leaders, Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia. The indecisiveness of Sajeeb Wazed Joy, Hasina’s son, is conveyed through cartoons of him, such as, as a middle-aged man swaddled in warm clothes, sipping his whisky, while going back and forth between saying, “My mother will return to the country, my mother will never return to the country.” That he is far away from the scene of the events in Bangladesh is conveyed by the fact that he is shown watching these scenes on television. The memes of Tarique Rahman just beg the chief advisor Yunus to not let him back, while older Facebook videos farcically sing praises of his bloodthirsty nature and general depravity.

Poetry expresses a gallows humour, with an element of pathos. A poem in wide circulation reads as follows:

I really wanted to be a metro station

At whose destruction it is difficult to hold back tears

I wanted to be a poll station

At whose burning there is a loss of 1000 crore takas

I wanted to be a data centre

For whom lament the people of the country

I wanted to be a city corporation waste dumping truck

Whose burning requires investigation by a six people committee

Instead, I was sent as a student,

Whose death does not bring about tears

Whose spilled blood does not produce a loss of 1000 crore takas

Whose death does not bring forth any investigation

Whose name is not even in the state’s loss and gain account books

Whose dead body is just an unknown number in the morgue

This, although, I had wanted to be so many things.

Rishi Kabbo (pen name), Bangladeshi photographer and traveller.

July 27, 2024

Of course, this is a reference to Hasina’s caterwauling over the destruction of property over that of lives in the aftermath of violence on July 24 but it still overall conveys a humanistic sense of the importance of human lives over all else.

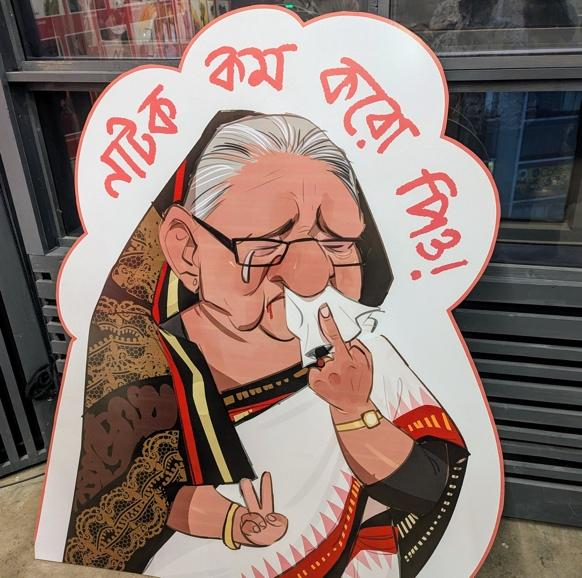

Political cartoons almost all seem to hone in on Hasina whose motherly face and figure are ripe for showing two facedness. As soon as Hasina was deposed, the satiric organisation Earki organised an exhibition at Drik gallery of such cartoons. These are clear digs at what I have previously called the grotesque figurations of power, whereas memes seem to be more complicated, even ambiguous in their expression, and I think deserve more attention.

Image 14. Credit: Earki

There is an interesting discursive distinction maintained between paintings, as in representations that are the property of those who created it and that have movability, as opposed to graffiti, the term used to refer to the artwork that springs up all over the country on every available wall. Those painting on the walls in fact refer to their own work as graffiti, not so much to indicate that it is being done without permission but to assert their claim upon territories possessed by others, as acts of reclaiming one’s neighbourhoods. Beyond the large crowds that gathered to march in the capital, which moves between celebration and menace as is the nature of crowds, this graffiti is probably the most profuse and effulgent expression of collective joy at the lifting of the clamp. These images suffuse social media, with commentators expressing their delight at the diversity of artistic expressions, by people largely unknown. A shared appreciation of the moment with strangers is itself the prompt for further joy. There is a celebration of stranger sociality that rises above that of imagined communities, that attempts to embrace genuine difference, such as that of pious others, and religious and ethnic minorities, and their defacement an alert of the need for more attention to possible lines of tension and cracks.

What we have here is perhaps a movement inadvertently-turned revolution. The politics that has found expression through the various artefacts is that of the right to free and fair elections, freedom of assembly, freedom of speech, acknowledgement of humanity, acceptance of diversity, and so on, the stuff of liberal politics. In the words of the various advisers in government, this amounts to reform of every institution such that they become people-oriented. All that is being asked is some patience and some time. This doesn’t amount to a fully articulated, much less progressive, political vision such as that of the reduction of inequality through say wealth redistribution. Yet, why is the call for more patience and time so portentous? They are to provide the pauses in which to insert small acts to interrupt the given, to produce something new. We may not know what that something is. This situation will likely produce no end of discomfort amongst the technocrats who run the world with their projections and policies, or leftists for whom a revolution worth its salt requires a clear revolutionary consciousness and who may thus never be satisfied by any movements in the world. But those who see what is happening in Bangladesh, and not just Bangladeshis alone, as a new chance to do and be otherwise, must live through this radical opening with alertness, being critical as necessary but without pronouncing final judgement, for as the French philosopher Delueze has warned us, judgement with its tribunals is the death knell of justice.

I would like to thank Naeem Mohaeimen, Kamala Visweswaran, Kunal Joshi and Shrobona Shafique Dipti for their helpful comments and general encouragement. All opinions and mistakes are exclusively mine.

Naveeda Khan is a professor at the Department of Anthropology in Johns Hopkins University.

Back to Homepage