As Bangladesh came into being, the post-liberation months showed a country lacking preparation for what was to follow. In the scramble for position, many compromises were made for the sake of “stability.” One such foundational error was defining the people of Bangladesh as only “Bengali” in the constitution, which set in motion the instabilities in the Chittagong Hill Tracts culminating in the Jumma (Pahari) indigenous people’s guerrilla war for liberation, the 1997 Peace Accord, and post-accord disillusionment. Another inconsistency came in the new constitution’s clause on restrictions on press “in the interest of the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign states, decency or morality.” In the Constituent Assembly debates, this was opposed only by Suranjit Sengupta of the National Awami Party (Moscow-aligned) and Manabendra Larma of Chittagong Hill Tracts (who also opposed the “Bengali” clause). In response, it was stated that the context of earlier repressive regimes in the Pakistan period was “not the context” of independent Bangladesh (Nazrul, 2022: p 122). The repressive apparatus that Pakistan had deployed was also carried over to the new state—for example, the Printing and Publication Ordinance (PPO).

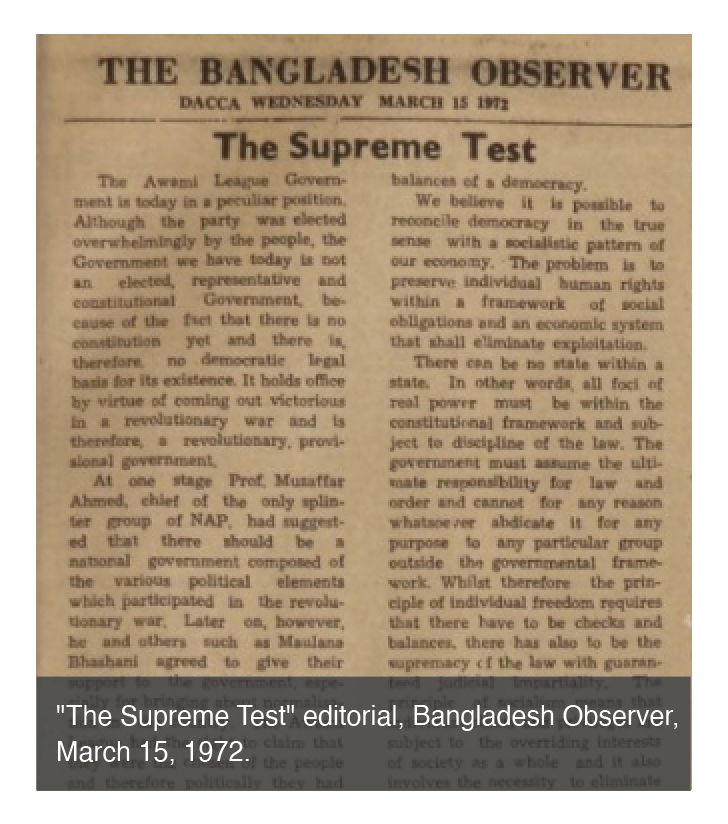

An early confrontation with the state came when veteran journalist Abdus Salam published his “The Supreme Test” editorial in Bangladesh Observer (March 15, 1972), which discussed the constitutional challenges for the new government. Some readers interpreted this editorial as stating that the state needed new mechanisms, not just the 1970 election results, as a framework for the country’s governance. The next day, the newspaper announced that Salam, who had been with Observer House for 20 years, had been “retired.” A month later, on April 26, the Novosti Press Agency of the Soviet Union released a commentary titled “Maoist activities in Bangladesh.” Displaying new modes of superpower meddling, Novosti demanded that the left newspaper Ganashakti, Maulana Bhashani’s Haq Katha and Enayetullah Khan’s Holiday be banned. Whether reflecting this diktat or using it as an excuse for wheels already in motion, Fayzur Rahman, the editor of Spokesman and Mukhopatra, was detained, and Haq Katha, Ganashakti, Mukhopatra, Lal Pataka and Banglar Mukh received notices asking why their license would not be canceled (Ullah, 2002).

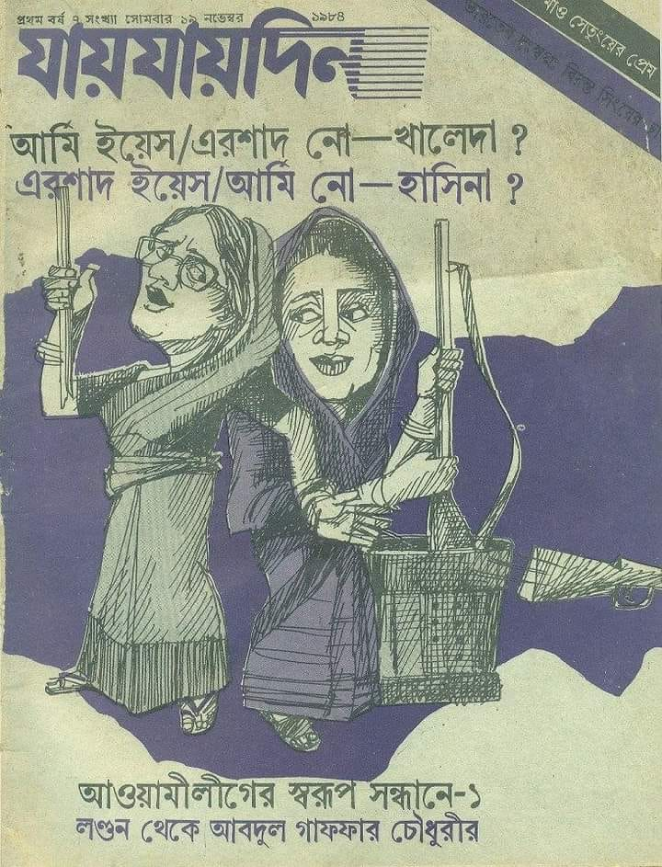

The new Awami League (AL) government was simultaneously handling an international balancing act (UN membership, repatriation of Bengali soldiers, war crimes trials, relationships with Islamic nations), and facing a strident opposition, mainly from a left energised by defections from the Awami League to form JSD (Jatiyo Samajtantrik Dal or National Socialist Party). On New Year’s Day 1973, police fired on protesters in front of the USIS (United States Information Services) building. When Dainik Bangla published a special report on the incident, Hasan Hafizur Rahman and Toab Khan were made OSD (Officer on Special Duty, a punishment short of firing) in retaliation.

Although the Pakistan-era PPO was repealed this year, Printing Presses and Publications Act (1973), which carried nearly identical powers (Riaz, 1993: p. 205) replaced it. The Second Amendment to the Constitution was also passed, allowing for the suspension of certain fundamental rights of citizens during an emergency. In one example of “emergency,” the Deshbangla office was raided after they published a news item claiming that the town of Rangamati would soon fall under the control of “armed rebels,” including indigenous Jumma people. 1974 saw the passage of the notorious Special Powers Act (SPA), which was used numerous times over the next decades against the media and opposition politicians (recipients included the same AL that passed the law). In a moment of unintentional irony, the Press Council Act (1974) was enacted in the same week as the SPA, although they contradicted each other on press freedom. Finance Minister Tajuddin Ahmed seemingly went against the SPA when he called for “healthy and fearless journalism,” but this gesture did not reduce the coercive power of the law.

Students protesting outside USIS (United States Information Service) after police firing, January 1, 1973. PHOTO: Ittefaq

1973-74 also saw the first blasphemy cases involving religion. These allowed a small gesture of strength by Islamic groups, which had been delegitimised by their unwavering support of Pakistan during the war. In 1973, Daud Haider published a poem in Shangbad where he allegedly satirised Prophet Mohammed, Jesus Christ and Gautama Buddha. A college teacher filed a case, and Dhaka saw its first postliberation Islamic party procession. Haider was taken into protective custody and later exiled to Germany. Soon afterward, social worker Engineer Enamul Haq published a leaflet that contained a reference to the Prophet’s wives, although Haq said it was not meant negatively. Death threats were issued, and processions were brought out, but the government dismissed it as “politics of anti-liberation forces.” Haq spent time in protective custody and was released.

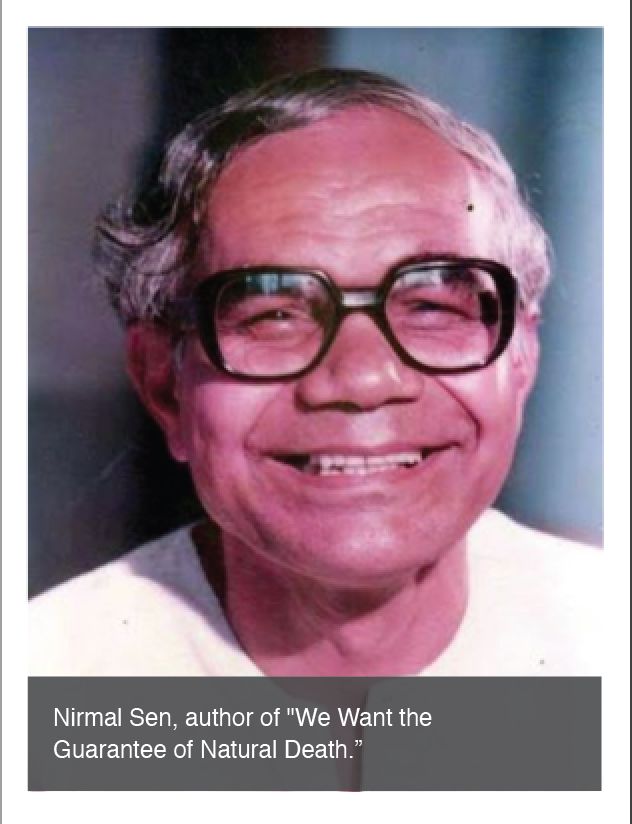

JSD became increasingly restless, and their gherao (surround) of the Home Minister’s residence led to deaths. In retaliation, the JSD-aligned Ganakantha newspaper was closed, and Acting Editor poet Al Mahmud was jailed—he was released a year later. The country was also shaken by the underground guerrilla campaign waged by the Maoist Sarbahara Party. The government’s response led to increasingly violent measures. As instability increased, goom khoon (disappearance murder) entered the lexicon, and Nirmal Sen wrote an essay in Dainik Bangla: “Shabhabik Mrittu’r Nishchoyota Chai (We want the guarantee of natural death).” He faced heavy censure from the government for this. In an even stronger protest, Rafiq Azad published a poem inspired by the 1974 famine: “Bhat De, Haramjada (Give me rice, you bastard).” He went into hiding after the government attempted to arrest him. By March 1974, repression had reached an intensity that a group of intellectuals, led by Ahmad Sharif, Sikandar Abu Jafar, Sardar Fazlul Karim, Badruddin Umar, Moudud Ahmed and others had formed the Committee for Civil Liberties and Legal Aid (Ahmed, 1983: p 263).

1975 was the year things fell apart. Increasingly besieged and isolated, the AL passed the 4th Amendment to the Constitution, which dissolved all political parties and created BKSAL (Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League or Bangladesh Farmer Laborer People’s League) as a unified political party. The Newspapers (Annulment of Declaration) Act (1975) announced the closure of 29 daily and 138 weekly publications. Only a few titles (e.g., Dainik Bangla, Bangladesh Observer) were allowed to continue. Numerous journalists signed applications to join BKSAL, although it was not clear whether this was voluntary. Among the few who refused to sign were Nirmal Sen (who had been censured the previous year), Kamal Lohani and Mahfuz Ullah.

Whether a free press in 1975 would have saved the government is unclear. However, the blanket suppression of media and political parties certainly did not stabilise the country, and the next chapter in the crisis was the military coup and assassination of Sheikh Mujib and his family on August 15th. On November 3rd, a counter-coup deposed the August group, and they were deposed in turn by a “Sepoy-Janata” mutiny four days later. The country seemed to be headed into a spiral of power struggles, until the cycle was broken by the consolidation of the Zia regime.