We need to clearly articulate what we mean by a discrimination-free Bangladesh

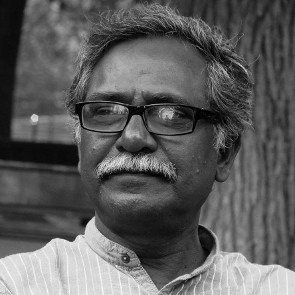

Anu Muhammad public intellectual and former professor of Economics at Jahangirnagar University, talks about the people’s aspirations for a just and equal society, the current ambiguity around the term ‘discrimination’, and the failure of the left in Bangladesh, in an interview with The Daily Star.

The rallying cry of the student movement that turned into a mass uprising was an end to discrimination. To what extent is that overarching vision being realised?

A deeply corrupt and oppressive regime, in power for a decade and a half, has been overthrown by the July uprising in Bangladesh. It’s important that we remember that a broad cross-section of Bangladeshi citizens of diverse religious, ethnic, gender and class backgrounds participated in the movement. At least a thousand killed in the lead up to and during the uprising, over a hundred of the deceased have been identified as labourers. Moreover, among the deceased students whose identities have been ascertained, a majority hail from working-class, peasant or lower-middle-class families. Of those injured, approximately 400 have suffered eye injuries, and many have lost limbs. The vast majority of these individuals are from impoverished backgrounds and lack the financial means to afford medical treatment. This dimension of the mass uprising has not received adequate attention thus far. The participation of the working class, the impoverished, and the marginalised sections of society in this movement, as well as their grievances and expectations, have not been adequately addressed in the discourse or discussions of policymakers, the educated leadership, or the interim government, almost two months after the uprising.

One common consensus that emerged from this popular uprising and the subsequent change in government is the desire for a Bangladesh free from discrimination. Despite ideological, political, generational, and social differences among the various organisations and individuals who participated in the uprising, there is a unanimous call for a society free from inequality and discrimination. Even the graffiti drawn on the walls conveyed such mature messages. The demand to end discrimination—so clearly expressed by the people on the streets—is yet to be articulated with equal clarity by those now in positions of power. The walls proclaim that all Bangladeshis, regardless of their religion—be it Muslim, Hindu, Christian, or Buddhist—should have equal rights. They assert that religion should not be used for political gain and raise questions about the rights of indigenous peoples. They demand gender equality, and an equitable Bangladesh. But what do the student leaders and those in the government mean by the use of the term ‘discrimination’? It is crucial to clearly articulate these demands and engage in a deep analysis of what we truly mean by a “discrimination-free Bangladesh”.

What forms of discrimination or inequalities are most prevalent in Bangladeshi society right now that should be addressed? If we are to go by the outcries on social media, it would appear that the most oppressed people in Bangladesh are male Muslims…

Yes, indeed, it would appear that way. But if we are deal with the issue in all seriousness, we have to understand that Bangladesh is grappling with various forms of discrimination, with class discrimination being a prominent one. Even neoliberal economists acknowledge the significant increase in inequality in Bangladesh. Over the past two decades, the real income or GDP share of the bottom 90 percent has declined. Income is now concentrated in the hands of the top 10 percent, with the top 1 percent capturing the lion’s share. The root cause of this inequality lies in the political economy.

We must discuss issues such as workers’ wages, the increasing commercialisation of education and healthcare, and the consequent alienation of a large segment of the population. Families are going bankrupt seeking medical treatment or educating their children. These processes—deprivation coexisting with growth—are causing a large number of people to become increasingly alienated. Those who are alienated, living in poverty and deprivation, were a significant part of the recent uprising. What will happen to them, and what programmes will be implemented to lift them out of their current desperation, is a crucial question.

The second form of discrimination is gender discrimination, not just between men and women but also involving other genders. This discrimination occurs both within and outside the home. We need to acknowledge the existence of various genders and respect them. Discrimination in areas such as property rights, employment, and mobility must be addressed. For instance, a woman’s dress or freedom of movement often faces various social restrictions and obstacles. Recently, we saw how a man was harassing a number of women for their clothing, or because they were sitting alone on the beach.

Next, we have the issue of ethnicity. Until now, the existence of ethnicities other than Bengali in Bangladesh has not been officially recognised in our constitution, society, or even among the political leaders. We see the recognition of indigenous peoples in graffiti on walls, but not in policymaking. Due to this discrimination, while Bangladesh as a whole may have escaped authoritarian rule, the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) remain militarised. The people of the CHT are still not free. Just as extrajudicial killings have been a significant issue in other parts of Bangladesh, they have also occurred in the CHT, but this issue is not being discussed openly.

Religious discrimination is another major issue. Not only are people of different religions facing discrimination, but even within the same religion, there are minority groups which are being targeted. It’s not just the dominance of one religion, but a specific sect within a religion that is being imposed. The events of the past month and a half, such as attacks on shrines, mosques belonging to different sects, and temples, are evidence of this. Minorities both within and outside of Islam are living in constant insecurity. The government has not taken sufficient measures to address this issue and reassure these communities that they are also protected. I recently spoke with some Hindu teachers who expressed their deep concerns about the safety of their relatives and friends. They reported incidents of their houses being demolished, looting, and job losses. It’s impossible to imagine a non-discriminatory Bangladesh where certain groups continue to live in a constant state of anxiety and fear. Not only that. recent mob killing, indiscriminate filing of cases and arrests are also matters of concern. The government needs to take a strong stance on this issue.

Does our current constitution adequately address the issue of discrimination?

We have engaged in continuous struggles—both before and after the Liberation War—because our aspirations of a just, discrimination-free society could not be fully reailsed. We’ve fought for our language, for the right to education, and against military rule, ethnic oppression, and inequality. This struggle has had an impact on a part of our constitution that prohibits discrimination based on race, religion, or gender. Additionally, the constitution states that the state is responsible for providing education and healthcare to all citizens. There’s also a provision that constitutional principles supersede other laws. However, subsequent amendments to the constitution have introduced numerous discriminatory, oppressive, and communal provisions, contradicting these fundamental principles.

The 1972 constitution was a paradox. On one hand, it spoke of equality and justice. On the other, it marginalised minority communities and centralised power, paving the way for greater authoritarianism. The dream of an equitable Bangladesh was born before 1971. The Liberation War of 1971 was also fought with this very dream, and a part of our constitution reflects this aspiration. Therefore, we must maintain this continuity. We must recognise that this struggle is not new, but rather a continuation of past efforts. This continuity must be reflected in the constitution, and we must clearly articulate in our constitution what we mean by an equitable Bangladesh.

Our walls proclaim that all Bangladeshis, regardless of their religion—be it Muslim, Hindu, Christian, or Buddhist—should have equal rights. PHOTO: Star

The left played an instrumental role in the 1969 mass uprising. What has happened to left-wing politics in Bangladesh since?

The 1969 uprising was the peak of left-wing politics in Bangladesh. Without the millions of workers from Tongi, Adamjee, and other areas coming to Dhaka, the mass uprising would not have reached its climax. This mobilisation of workers was primarily led by the left. The same was true in Chittagong. The dominant force in student organisations at that time was the left.

After 1969, during the Liberation War of 1971, a clear division emerged in our national politics. One faction, particularly those involved in Islamic politics, sided with Pakistan and committed war crimes. On the other hand, the Awami League and other forces, particularly those aligned with nationalism, and the left fought for liberation. This nationalism was largely Bengali nationalism, which was not all-inclusive. Those in the left camp fought for liberation and talked about socialism. However, after independence, a section of the left merged with Bengali nationalism and essentially equated left politics with Awami League politics. This was a mistake. Left politics and nationalist politics are not the same. There were also other left-wing groups who did not side with the Awami League, but they faced severe repression from 1972 onwards. Their discourse also had flaws.

After the 1975 coup and the subsequent martial law, those who came to power included individuals who were pro-Islamic and anti-liberation war. This led to a narrative of liberation versus anti-liberation, which continued throughout the 1980s and after. Consequently, the significant issue of class struggle was overshadowed. This was a major failure on the part of the left. They could have regrouped in the 1980s but failed to do so. In the 1980s, the anti-Ershad movement led to political mobilisation, and an alliance formed under the leadership of Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia. A section of the left aligned with Hasina, while another aligned with Khaleda. This was a suicidal act. The left failed to maintain a distinct identity and instead chose to follow either Hasina or Khaleda. Only a small, insignificant left-wing faction remained independent.

Another threat came from various neoliberal economic policies, such as structural adjustment programmes and World Bank policies. These policies led to the dismantling of major industrial bases in Bangladesh. I believe that the World Bank’s suggestion to privatise or shut down Adamjee and other jute mills lacked any sound economic logic. In my opinion, they had a political agenda too. They wanted to dismantle the organised working class. They aimed to eliminate industries where the working class could unite. Previously, places like Adamjee had living arrangements for workers. The left’s main base was in those jute, textile, and sugar mills. Those industries were dismantled, starting in the 1980s and concluding around 2002. This was another significant blow for the left.

The left leaders failed to adapt to the new shape of the working class, which was now dominated by the garment industry and informal sector. Secondly, their failure to differentiate themselves from the politics of nationalism or religion weakened the left base in Bangladesh. Furthermore, many left leaders joined the Awami League, while another set joined the BNP or the Jatiya Party, which was disastrous. If we look at the leadership of the BNP, Jatiya Party, and Awami League, we’ll find many former leftists. In fact, former leftists have been ruling the country for a long time. However, they have not advanced the cause of left-wing ideology. The growth of the left parties has stagnated.

Do you still see any hope for the left in Bangladesh?

When we hear the phrase “discrimination-free Bangladesh” or see it written on the walls, it’s essentially a left agenda. If we can articulate what it means to talk about equity and oppose inequality, then we must inevitably move towards left-wing politics. Without the left, the fight against inequality cannot progress. Right-wing politics, or any other form of politics, inherently promotes inequality. Whether it’s religion-based politics, nation-based politics, or nationalist politics, they all promote inequality. The dominant neoliberal economic model is also inherently inequitable. I believe that the aspirations of society are fundamentally left-leaning. And the discourse of the majority who are involved in movements is also left-leaning. However, this is not articulated or recognised in the politics of the leadership. Right-wing politics, on the other hand, cannot represent people’s aspirations. By partially addressing issues of inequality, they essentially deceive the people.

How would you evaluate the interim government’s role in addressing some of the concerns you have highlighted?

A significant portion of the killed and injured during this uprising came from working-class families, and we haven’t yet seen any substantial government attention regarding the full protection they need. When we look at the government’s response to labour movements, it becomes clear that their perspective on workers hasn’t changed from the previous government. They consistently adopt the same stance: whenever there’s a labour movement, the government sides with the employers, echoing the employers’ language and arguments. And they often resort to blaming imaginary external conspiracies.

Whenever there’s a possibility of change created by peoples’ movements or mass uprisings, various social groups try to get their dues. However, the demands of the deprived people must be addressed. While there may be external influences fuelling the workers’ movement, it’s undeniable that they harbour deep resentment. We must understand the reasons behind this resentment. It stems from issues like unpaid wages, various forms of abuse, mass layoffs, and the non-payment of wages to those who participated in the labour movement. These are just some of the many grievances that contribute to their anger.

There are various gender discrimination and gender issues in society, and the government is showing no signs of addressing them. There are also serious problems with public education and healthcare. There is a lack of attention to mega projects that are a burden on our economy and pose significant risks to our environment. While this government cannot solve everything, its perspective should be clear. For instance, projects like Rampal and Rooppur pose significant risks to Bangladesh if we don’t find a way out. I’m not saying this government can cancel them immediately, but they should at least prepare the ground to do so. From the government’s statements, it seems they plan to continue with all existing agreements. But if that’s the case, what will change? The previous government signed many harmful agreements that went against national, public, and environmental interests. If these agreements continue, then the politics will also remain the same. These are major concerns for us. We haven’t seen a significant enough difference in the government’s approach to these issues.

Back to Homepage