The uprising of cartoons

Simu Naser

It was the middle of 2010. At the time, I was the editor of a popular weekly satire magazine for a daily newspaper. One day, the editor approached me with a cautious suggestion: if possible, we should avoid publishing caricatures that mocked the prime minister. The repercussions of such publications were potentially severe and unmanageable.

This left me deeply disheartened. We were already constrained in our ability to publish certain topics, and now, this restriction further narrowed our scope. What were we to publish? The presence of Shishir Bhattacharjee’s cartoons on the newspaper’s front page began to diminish, and the space allocated for cartoons in other dailies also shrank. Time passed, and eventually, it became impossible to publish any cartoons mocking the prime minister. The situation escalated to the point where the newspaper was forced to shut down its satire magazine altogether— for the second time. Later on, anyone who dared to mock Sheikh Hasina on social media or other platforms often faced imprisonment, courtesy of the notorious Digital Security Act (DSA). Cartoons, satire, and humour couldn’t touch the prime minister.

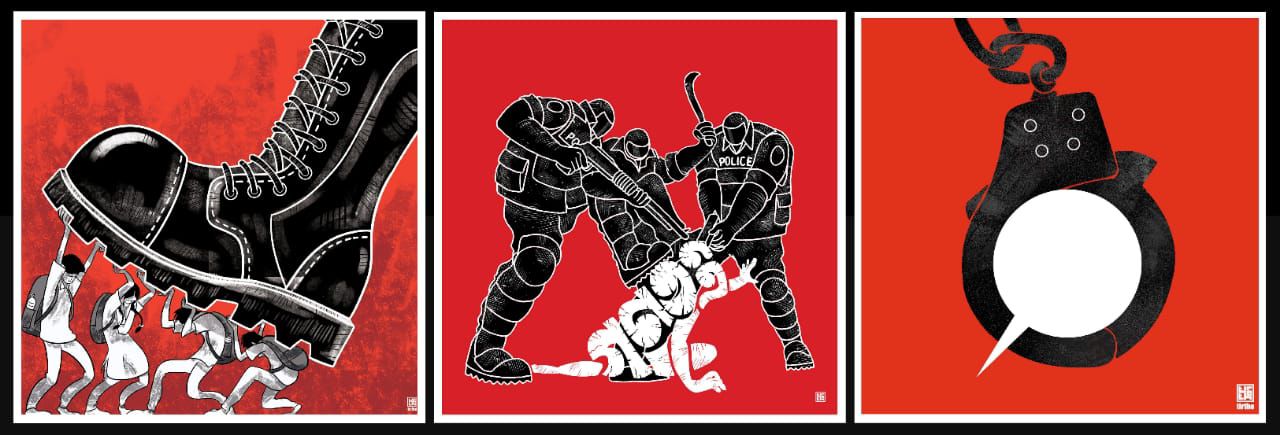

Visual: Tirtho

Satire and humour have a peculiar quality: the more repressive the environment, the more clever, nuanced and referential humour begins to flourish. Perhaps this is why some of the finest political jokes in history emerged during the Tsarist and Stalinist eras of the Soviet Union. In Bangladesh, as social media gained prominence, meme culture began to take root. Satire evolved, with new ambiguous phrases like "Uganda", "Nam bolle chakri thakbe na (I’ll lose my job if I say the name)", and "You know who" gaining popularity online. Yet, apart from a few scattered publications, political cartoons have nearly vanished from Bangladeshi newspapers.

This is not to say that the country’s history of political cartoons lacks a strong foundation. On the contrary, during the 1952 Language Movement, when Bangla was under threat, Kazi Abul Kashem (Dopiyaza), the subcontinent’s first Muslim cartoonist, inspired many with his “Haraf Khedao” cartoon. Similarly, Kamrul Hasan’s famous caricature of Yahya Khan—incorporating the line “These beasts must be eliminated”— became an iconic image, and his sketch of the autocratic Ershad—with the comment “Desh aj bissho behayar khoppore (The country is in the hands of a shameless person)”—remains a significant document in history. Artist Rafiqun Nabi, known as Ronobi, used his character “Tokai” to comment on social disparities and politics for decades. Other notable contributors include Qayyum Chowdhury and Zainul Abedin. Shishir Bhattacharjee, in particular, significantly transformed the landscape of political cartoons in Bangladesh with his work often becoming the talk of the town. During that period, artists like Huda, Kuddus, Bipul, and Nazrul were also actively drawing. However, as a new generation of cartoonists began to emerge, the country entered an era of extreme restrictions on freedom of expression. These young cartoonists, unable to find space in newspapers, shifted their careers to other media. The arrest of cartoonist Kishore added a new layer of fear among them.

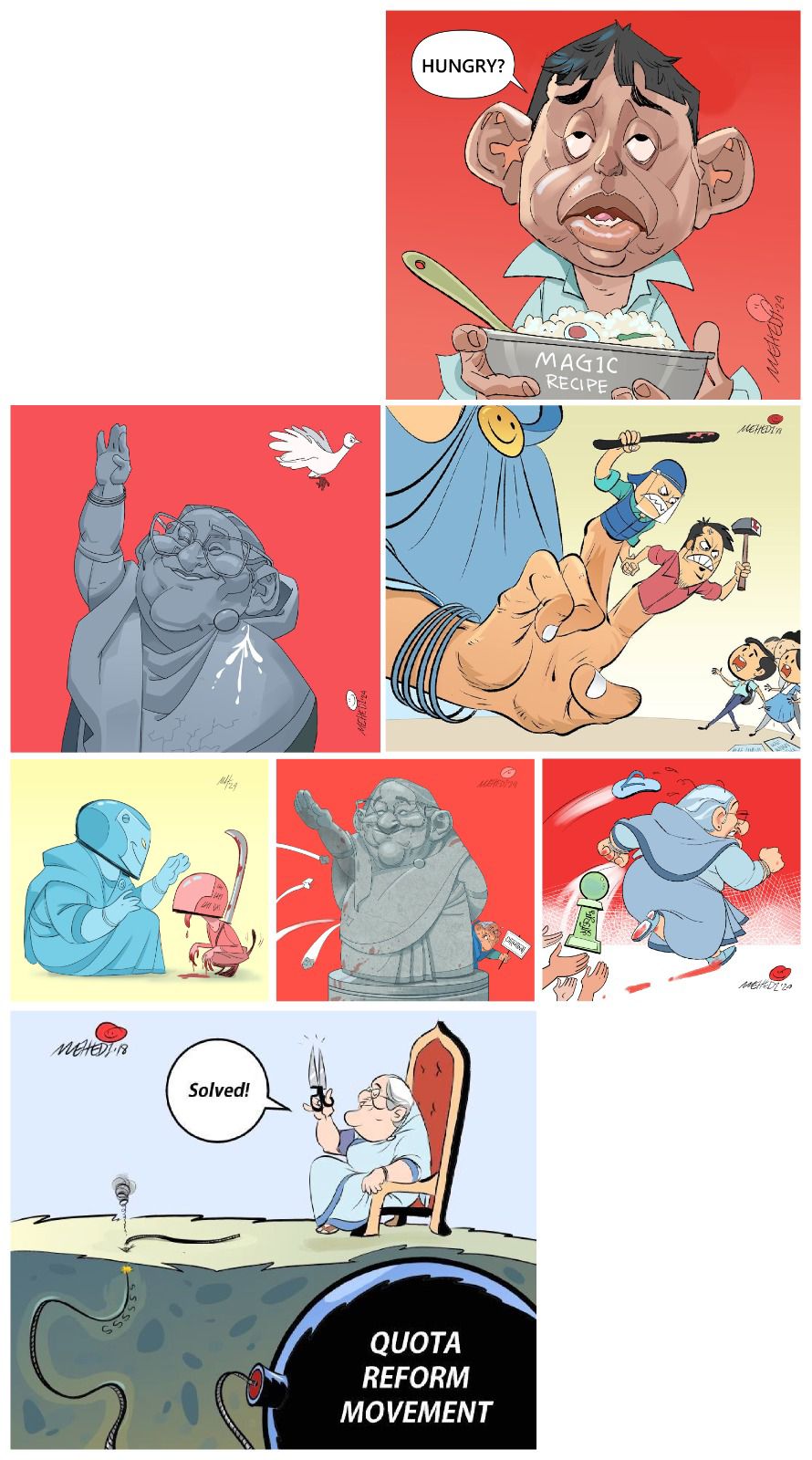

Visual: Aaron

I have always been a huge admirer of political cartoons. When I left the newspaper and decided to start the online satire publication Earki, I felt compelled and committed to regularly feature political cartoons. However, by then, almost all the familiar artists had stopped drawing them and had moved on to other fields. Among the few remaining, Mehedi Haque continued to draw regularly. We decided instead of waiting for the older generation to reemerge, it was time to inspire and encourage new talent, so we organised a political cartoon exhibition and a few workshops to discover new cartoonists.

Visual: Amit B

In March 2023, we launched the exhibition along with three days of workshops. The exhibition featured around 150 selected political cartoons, spanning from 1952 to the present, highlighting significant moments in Bangladesh’s political history. It covered issues around national politics, civil rights, and freedom of speech. Veteran artists like Rafiqun Nabi and Shishir Bhattacharjee attended to speak with the young cartoonists. Over three days, 40 young cartoonists created numerous drawings, engaged in discussions, listened, and debated, and the collective sparked fresh courage. We discovered a number of new cartoonists, several of whom continued to draw regularly with us and on social media.

Later, before the 2024 national election, we organised another exhibition called “Election the Selection”, issuing an open call for cartoons. The response was astonishing. Incisive, satirical and politically aware cartoons poured in from university students and new cartoonists, proving that the youth had not forgotten to draw. In fact, behind the scenes, cartoonists have always been drawing and remaining vigilant. It was the editors of mainstream media who were constrained by self-censorship and unable to make room for political cartoons.

Visual: Apu

We selected 100 cartoons from nearly 500 submissions and held the exhibition at Drik Gallery, which attracted a large audience. This demonstrated that public interest in cartoons has not waned. In the era of reels and memes, enthusiasm and demand for political cartoons remain strong, indicating that they are poised for a significant comeback.

However, I never imagined they would return in this way. As the quota movement grew into a mass uprising, cartoonists ignited like gunpowder after July 15. Shocked by images of Chhatra League violence against protesters and videos of deaths caused by police, cartoonists were the first among artists to spark protest. Long-unused and rusted pens came alive like sharp blades. For the first time in a long while, cartoons directly depicted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina—her image marked with bloodstains and signs of murder.

Visual: Mehedi Haque

A striking cartoon of Hasina praising the murderous helmet-wearing Chhatra League members made rounds in social media and online forums. Another artist depicted Abu Sayeed standing with his chest out. Within hours, these cartoons spread like wildfire on the internet. Facebook Feeds were flooded with cartoons under the themes “Killer Hasina” and “Autocrat”. These drawings became the primary medium for expressing intense public frustration, pain, anger, and outrage. The fear of reacting to even mildly critical posts due to the Digital Security Act seemed to crumble.

The use of cartoons in mass uprisings is a long-standing tradition, but the sheer volume of cartoons created in the last 20 days of July 2024 seems to be unprecedented in the country’s history. Many of these cartoons were produced by entirely new cartoonists, some of whom may have been drawing their first political cartoons. Yet, their work displayed a level of sharpness, awareness and expertise that belied their inexperience. Notably, many cartoons used a colour palette dominated by red blood, reflecting the profound impact of the regime's violence on the artists.

After Sheikh Hasina and the Awami League government’s downfall, we organised an exhibition of 175 selected cartoons from the uprising at Drik Gallery. Due to public demand and the sheer number of visitors every day, the exhibition was extended by another week, and was a reminder that cartoons remain a powerful medium for expression and rebellion. Readers and viewers now hope that a new generation of cartoonists will illustrate a boundless, new imagination of Bangladesh—a picture that will speak more than a thousand words.

Just as 2024 will be remembered as the year of mass uprising, it will also be remembered as the year of political cartoons.

Simu Naser is a journalist and political satirist. He is the editor of earki.co.

Back to Homepage