The Tyranny of Tagging: Dismantling the fascist, discursive weapon of labelling

Nasrin Khandoker

Tagging a group of people with a derogatory name and thereby erasing the individuality of its members is one of the most effective ideological tools used by fascists. It is the starting point of the process of racialisation, leading to the construction of labels that are often associated with stereotypes, discrimination, and social hierarchies. Labelling a group of people with a derogatory name is also the first step to denying their humanity.

In the 90’s, the term “inyenzi,” originally used by Tutsi exiles to describe their disciplined armed movement, was twisted by the genocidal Rwandan government into a derogatory label for all Tutsis, equating them with cockroaches. Through this terminology, the Tutsis were no longer considered human, and this dehumanisation made it easier to justify mass murder during the 1994 genocide, as Tutsis were portrayed as a ubiquitous threat.

In this century, terms that have stripped people of their individuality and humanity include labels like “terrorist” in the aftermath of 9/11 and the “war on terror,” as well as “Hamas” in the context of Israel’s ongoing genocidal war against Palestine.

In Bangladesh, while not necessarily driven by genocidal intentions or nationalist community-building, the practice of labelling individuals—whether positively or derogatively—has been normalised in political debates since the country’s birth. For instance, “muktijoddha” is an unequivocal category of sacrifice, heroism, and high moral ground while “razakar” is the opposite, the ultimate traitor to the nation. Although some people do not fit into these binary categories, they have become socially, politically and, to some extent, legally fixed as binaries. Their stereotypical binary images have also been constructed by the media.

Since the introduction of Bangla typing on blogs, the Bangla blogosphere began to be saturated by some new name tags, such as the binary opposites of shushil and chagu. Shushil (civil society members) was the derogatory label given by online trolls to people claiming to be the upholders of the conscience of the Liberation War and demanding war crime tribunals. On the other hand, the term chagu (goat) was a derogatory label used by Bangalee nationalist trolls to describe individuals who are perceived as overly sympathetic to the accused war criminals, particularly Jamaat-e-Islami and its supporters. The online discourse between them was characterised by aggressive rhetoric, with both sides employing sexist language and personal attacks to undermine the other.

Although the term initially applied to anyone who participated in the Shahbag protest, it was later used to describe anyone who demanded the punishment of the accused war criminals and, therefore, was assumed to be the enablers of the Awami League.

PHOTO: Star

In 2013, the Shahbag movement added a new dynamic to this discourse. Although initiated by online activists, the Shahbag movement incorporated plural political groups in the beginning. However, it soon became the enabler of the Awami League and its autocratic regime. The Shahbag movement sparked intense name-calling and accusations. The term “Shahbagi” was used derogatorily by the Islamist online trolls who were sympathisers of the accused war criminals. Although the term initially applied to anyone who participated in the Shahbag protest, it was later used to describe anyone who demanded the punishment of the accused war criminals and, therefore, was assumed to be the enablers of the Awami League.

On the other hand, the label chagu has been used by the Bangalee nationalists, not only against Islamist sympathisers of the accused war criminals, but to label and discredit dissenting voices, even among the participants of the Shahbag movement. For example, the participants who were critical of the Awami League were labelled as shushil chagu, implying that they were traitors to the nationalist cause and against the punishment of the accused war criminals.

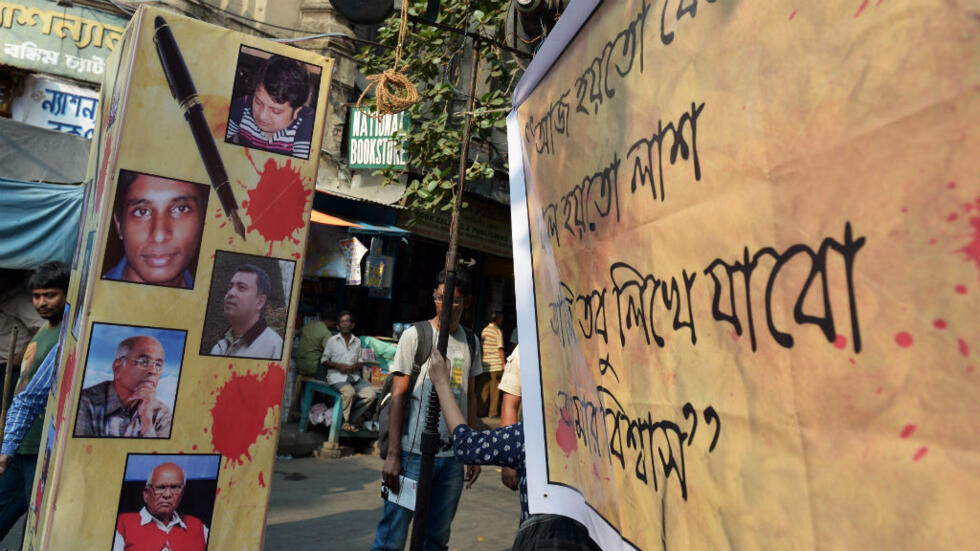

At this time, the term nastik (atheist) became another category that crossed a limit of apparently harmless name-tagging. In 2013, some Islamist groups accused certain bloggers of hurting religious sentiments and labelled them nastik, which became the first step towards denying their humanity. This labelling eventually led to the murdering of bloggers. From 2013 to 2016, at least 30 bloggers were killed in Bangladesh, and three others were injured. Bloggers and activists were often accused of offending religious sentiments through their online engagements, making them “legitimate” targets for attacks which were often indirectly supported by the supposedly secular Awami League government through their victim-blaming.

By delegitimising Hasina's labelling, the protesters dismantled the government's ability to weaponise it, stripping the term of its intended power. PHOTO: Star

During the Awami League government’s progression towards fascist rule, their ideological weapon was the term Jamaat as the boogieman to silence any dissent. Capitalising on a fear of fundamentalism by labelling numerous people “Jamaat” and arresting and abducting them served as the most potent tool for creating the hegemony of Awami fascism. In addition, a few labels were also used to rebuff criticism of the government. One such was Baamati, which combined the term baam (left) with Jamaat. This label was particularly used to dismiss anyone from a socialist position criticising government repression and corruption. The labels such as Jamaati, razakar, or Baamati have been indiscriminately used to deny different forms of resistance against the Awami fascism.

The recent quota movement in Bangladesh, which evolved into an anti-government revolutionary force, gained significant momentum by challenging the fascist manipulation of the terms razakar and muktijoddha. While the term muktijoddha has been associated with honour, bravery, and national liberation, symbolising the highest moral ground in the country’s history, the Awami League has distorted this term, using it in the quota system to reward those loyal to the regime rather than those truly deserving. This manipulation served to perpetuate nepotism and favouritism, benefiting a select few, while excluding qualified others. The movement began to put an end to this fascist practice of rewarding supporters by twisting the system.

In response, the regime once again used the term razakar to dismiss protestors’ demands. Sheikh Hasina labelled them as the “razakars’ grandchildren,” implying that they were protesting to take away the rights of the muktijoddhas’ grandchildren by demanding a repeal of the muktijoddha quota. When Hasina attempted to discredit their legitimate demands and portray them as enemies of the state, instead of succumbing to this insult, the protesters responded with a powerful act of defiance: they sarcastically and defiantly embraced the label of razakar, exposing how the regime uses such terms to stifle any form of dissent or criticism.

This marked one of the most rebellious moments in the country’s history. By delegitimising Hasina’s labelling, the protesters dismantled the government’s ability to weaponise it, stripping the term of its intended power. The regime’s propaganda machine, which sought to crush the movement with these derogatory labels, failed spectacularly. In doing so, the protesters achieved a symbolic victory, reclaiming the language used against them and turning it into a tool for their own cause. It was a strategic victory that echoed the broader struggle against tyranny and oppression, showing the power of resistance in the face of fascism.

However, soon after the fall of the fascist regime under Hasina, the practice of labelling individuals to strip away their individuality has resurfaced and taken a troubling new turn. In the aftermath of Hasina’s rule, a fresh wave of politically charged labels have emerged online. Terms such as baam, Shahbagi, shushil, and fascist dalal are now being used carelessly and indiscriminately to target members of civil society, often with little regard for their political position or intellectual contributions. Civil society members—including activists, intellectuals, and ordinary citizens—are increasingly being branded with labels simply for expressing independent thought.

“Baam” (which refers to the left) is now being used to dismiss and undermine the efforts of those who have long resisted the fascist regime of Hasina. While it is true that some left-wing parties supported the authoritarian regime, the term baam is now being used indiscriminately. Many activists who have no connection to the politics of the previous era are being dismissed simply because they have a socialist orientation, despite having been consistently vocal against discrimination and oppression caused by every regime.

A key example of this is the Dhohojatra (a parade of rebellion) led by Professor Anu Muhammad on August 2, where he demanded that Hasina step down. This powerful parade and the demand provided significant momentum in the fight against the government. Yet, after the regime change, Anu Muhammad is frequently dismissed on social media by trolls who label him or those associated with his politics as baam.

This new wave of labelling is dangerous because it continues the fascist practice of reducing people to simplistic categories, denying their individuality and complex perspectives. Instead of encouraging political dialogue or a focus on healing after the fall of the regime, it fuels a culture of denial, suspicion, and hostility. As in Hasina’s time, these labels are used to silence opposition and tarnish reputations, showing that labelling remains a destructive force in Bangladesh’s political landscape. This reckless name-tagging homogenises people and risks dehumanising them, stripping away their individual rights.

In the fragile post-regime period, as Bangladesh tries to rebuild after years of damage to state institutions and civil society, such labels can cause further harm. By branding individuals with simplistic political categories, society risks repeating the exclusion and repression of the past instead of focusing on rebuilding a democratic, inclusive future.

Dr Nasrin Khandoker is a social anthropologist, feminist and postdoctoral researcher at the University College Cork, Ireland.

Back to Homepage