Mediating the July massacre

Kajalie Shehreen Islam

“I am extremely disturbed by how the media are being used to legitimise this mass killing,” read a text message from my former student, who is a journalist working for a local television news channel, on July 21.

According to a preliminary report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), published on August 16, at least 650 people were killed in Bangladesh during July’s movement-turned-massacre. Of them, 400 were killed between July 16 and August 4, and 250 on August 5 and 6, following the resignation of Sheikh Hasina from the post of prime minister and the fall of the Awami League government. Many of those injured during this year’s quota reform movement have subsequently died, and lists by local human rights organisations have put the number of dead at over 800. Unofficial estimates put the number of dead in the thousands, including not only unarmed students at peaceful protests, but also passers-by going about their day, as well as children who were sitting at home by the window or playing on rooftops.

Thinking back to the media coverage of the last two weeks of July and the first week of August, however (when I watched more local news at a stretch than I have in years), the movie playing in my mind consists of flashing, recurring images: Sheikh Hasina at press conferences labelling quota reform protesters first as razakars, and later as terrorists; former Awami League General Secretary Obaidul Quader calling upon Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL) activists to give a fitting reply to those who (apparently) labelled themselves razakars; former Additional Commissioner of the Detective Branch (DB) of Dhaka Metropolitan Police (DMP) Harun or Rashid stating that the protest coordinators were being held in custody for their own safety; former Law Minister Anisul Huq claiming that the government had had fruitful dialogue with the protesters; former Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan claiming that no children had been killed in the violence; Sheikh Hasina again, crying over the decades-old loss of her own loved ones; former Minister of State for Information and Broadcasting Mohammad A Arafat talking about the restraint the government had shown so far and how so many bullets were still left to be used; the arson, looting, and destruction of state property by “BNP-Jamaat-Shibir-razakar-terrorists”; more of Sheikh Hasina crying over the destruction at a couple of metro rail stations, over the burnt down Bangladesh Television (BTV) buildings, over injured BCL activists; and of course, Sheikh Hasina reiterating how no one knew the pain and grief of losing loved ones better than her.

But where were the mothers who had lost their young sons just days before? Where was the father whose six-year-old daughter died in his arms as he rushed to bring her down from the rooftop where she was playing, lest she be killed by the helicopters shooting from above—and she was indeed shot in the head, while he was carrying her away. Where were these stories in the media, and particularly the electronic media, which could be anywhere and everywhere following the protests, the protesters, the violence, the retaliation, the resistance, and the resilience? It was unquestionably the duty of the mainstream media—especially during the internet blackout when people had no other source of news to turn to—to provide people with actual, factual information about their country, their people, and their government.

Unarmed students being shot in the chest. A student who was distributing water among protesters being killed 15 minutes later. Another student shot and thrown off a police vehicle, left to die. A young man hanging on for dear life to the edge of a building, shot until he finally let go and fell. A man shot in the leg while still trying to drag his injured friend to safety, but the friend being shot again, at closer range this time, and knowing that he was dying, asked his friend to let go, which he finally did, leaving him and limping away to escape. We saw all this first on social media, images and footage which robbed us of sleep at night and any peace of mind during the day.

The night before the fall of Sheikh Hasina and Awami League, one of my students called me in a frantic state. BCL goons with machetes had attacked her, her mother, and two of her friends in their own neighbourhood. Her brother had been beaten up, picked up, taken away, and beaten up some more. When I spoke to her again later, she cried and cried as she recounted her brother’s injuries to me—both his hands were broken. But she cried the hardest as she told me that the whole time, the police stood by, watching, and did nothing.

Thousands of stories like these never made it to the mainstream media. Hundreds of injured are still in hospital. Numbers of dead have, as usual, turned into statistics rather than stories of lives lived and unjustly taken. Even journalists were killed and injured in the violence. But the media only gave us statements about “normalcy”—how law and order was being maintained during the curfew; how, at various points, the protesters had supposedly negotiated with the authorities and called off the movement; how important people were urging students to go back home and to the classroom; how the only violence being perpetrated now was by BNP-Jamaat-Shibir-razakar-terrorists.

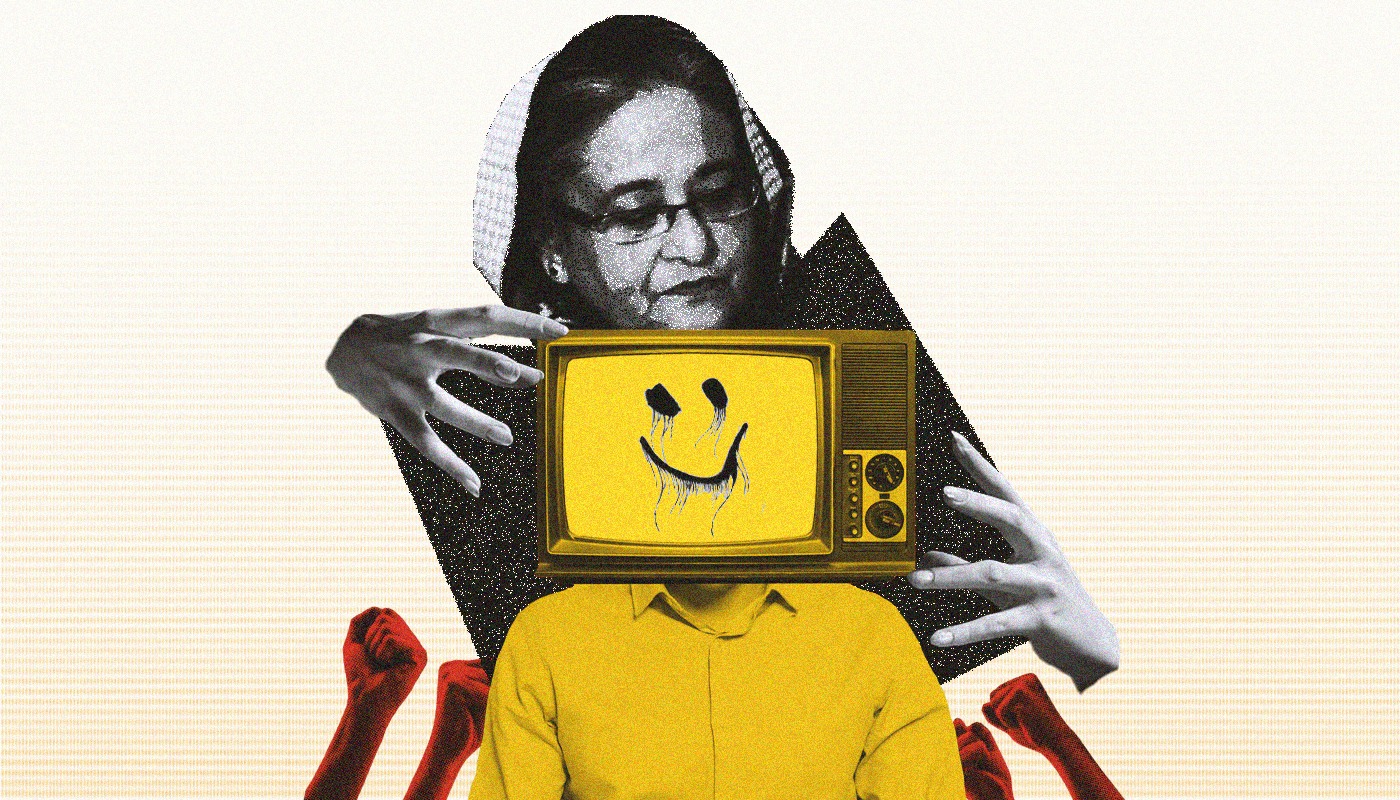

Throughout the July massacre, the bulk of mainstream media coverage was of government leaders and officials spewing their propaganda repeatedly, shamelessly, endlessly. Only a handful of cases, after being shared on social media, were covered by the mainstream media when they could not be ignored any longer. But even then, the coverage was minimal.

By not reporting on these atrocities, by not holding accountable those responsible for committing them through their orders and their actions, the media did indeed legitimise them. For the past 15 years, the media helped shape and disseminate the discourse of the powerful about who was “pro-liberation” and who was “anti-liberation”; about who were the patriots and who were the enemy; about who deserved protection and who it was acceptable to vilify and persecute. During the July massacre, what people had come to expect from state-owned television and media was also what they got from private television networks and many newspapers because they were, in essence, state-controlled. It was only because the people “took the media into their own hands” through social media that they were able to fulfil the role of the media to inform, to educate, and to persuade.

During the internet blackout, all people had were the mainstream media. What they themselves experienced or witnessed with their own eyes, and even recorded on their own cameras, they had no way of sharing. Many people’s phones and cameras were seized and later destroyed in order to prevent them from sharing what they had captured once the internet was back, demonstrating just how powerful the roles of social media and the general people were during the movement. Failed by the media, people turned to social media; and when that was largely disabled by the government, they worked their way around it through virtual private networks or VPNs. People went beyond sharing information by producing memes, reels, artwork, poetry, music, and skits. Online and offline, people came together, in protest, in resistance, in an awakening. And the government that refused to give them their rights came crashing down like a house of cards.

Alongside the wrath against the authoritarian regime was people’s outrage against its media, which became apparent as soon as the government fell. Those media outlets perceived to have acted as the state’s propaganda machinery over the past 15 years, and especially during the past month, were vandalised, including Somoy TV, Ekattor TV, and ATN Bangla, among others. Journalists associated with them have been called out—some even attacked, and some have been arrested on various charges. The line between freedom of speech and expression, and the freedom to design and disseminate propaganda can become blurry and requires addressing. But the remedy is not to suppress the media all over again. While some media outlets blatantly towed the government line over the past several years and even in July and the first week of August, others have had to navigate the political reality of authoritarian rule in order to survive. Many of the faces we see on screen or the by-lines we read in newspapers are not the ones who determine editorial policy, and not everyone has the luxury to quit on moral grounds, though some journalists have resisted at various times. Threats, and threats realised, such as through filing of the 2018 Digital Security Act against several journalists, served to intimidate many, and almost did away with investigative reporting in general, and any criticism of the government in particular. Except for the shamelessly partisan, many Bangladeshi journalists themselves felt trapped in their jobs where they could not speak the truth, let alone speak truth to power.

Trust in the media has eroded worldwide—the highest percentage of people who trust the news media most of the time was in Finland, at 69 percent in February of this year, according to Statista. The lowest was in Greece at 23 percent. There were no statistics available for Bangladesh in this particular study, but the lack of trust has been violently visible. The right to freedom of expression and information through the media must be guaranteed, and no one, including state officials, should be above criticism. For this, it is essential that media ownership and control be free from political as well as corporate influence, both of which have been eating away at the integrity of our media.

An article published on University College London’s (UCL) The Constitution Unit blog on the role of media in democracies and why it matters lists the features of a “free and healthy” media: independence, pluralism, impartial media outlets, high journalistic standards, and the complex issue of regulation of standards balanced with the need for media independence. The article also lists risks which the media face, including threats to broadcaster impartiality, threats to media independence, polarising content, weakened local and investigatory reporting, disinformation and misinformation, and monopolies.

For Bangladeshi media, the aforementioned “risks” seem to have become its characteristics, and the features of a free and healthy media perhaps seem remote and idealistic. Long-practised self-censorship and the suppression of disagreement/debate/dissent will take time and practice to overcome. But independence must be exercised, balance and objectivity maintained, investigative reporting revived, dis/misinformation countered, and monopolies broken down. It is only by ensuring independence of the media, by allowing diversity of views, encouraging impartiality, and rewarding high journalistic standards that a truly democratic media can be established for a truly democratic society.

The purpose of media regulation is to facilitate all the above, not to suppress media freedom. It is past high time that we de-normalise the maladies which have become the most common characteristics of the Bangladeshi media, and work towards establishing and strengthening the qualities of a free and healthy media appropriate to, and necessary for, a true, healthy, and functioning democracy.

Kajalie Shehreen Islam is an associate professor at the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism in the University of Dhaka.

Back to Homepage