How we go about the Bangla Spring now will define its future

Altaf Parvez

Before the Bangla Spring, there was a perception around the world that in the era of “surveillance states”, transformative politics cannot emerge victorious. This, after all, was the era of spies, of reactionists, of populism—an era of Pegasus’s dominance. But if George Orwell was alive, he would have looked on in awe at how the people of Bangladesh have flipped “1984” in 2024. This is why this mass uprising has communicated new hope among the oppressed peoples of the world. They are now thinking, “Victory is possible.” As a result, there is a global necessity to protect this uprising in Bangladesh. At the same time, conservative attempts to discredit and derail it are also nothing unnatural.

Lethargy in civil administration

Already, the Bangla Spring has faced some troubles within the country. There is some scepticism in society about the strength of the government that has been formed following the uprising. The government is facing a multidimensional crisis as it struggles to project an image of power. Perhaps as a byproduct of this, the administration has not been as active as expected. The activity in police stations has not resumed in full swing, and the police are yet to conduct patrols like they used to. Incidences of stealing and hijacking are on the rise.

The fire incidents in Gazi Tyre and Pran-RFL factories spread terror among industrialists. In Gazi Tyre, looting took place for an extended period of time, after which it was set on fire, yet no effective preventive steps were seen. The fact that industrialists, afflicted by fire and terror, are having to go around asking for security in different places is definitely a matter of embarrassment for the interim government.

At the same time, the pre-announced destruction of shrines in various places is spreading fear in rural society. No one in the administration seems to be considering it their responsibility to stop these attacks. Although warnings of legal actions against those involved were issued by the chief adviser’s office, their effects were negligible.

In fact, even during the terrible floods in Greater Noakhali, the civil administration was unable to assume the role of leading the coordination efforts. Instead, people had to place their trust in the army and students. Even though hundreds of trucks filled with relief goods left Dhaka, a tremendous weakness was observed in coordination among involved groups, especially with regard to prioritising marginal areas that needed the relief on an emergency basis.

Many volunteers were seen distributing relief in places close to highways and big roads, taking some pictures, and coming back. It’s as if there was nothing to be done about getting rid of the floodwaters other than distributing relief and blaming India! The people of Greater Noakhali and surrounding areas were in an unthinkable state of suffering because of waterlogging.

People don’t want to lose trust

Similar to Noakhali, the spirit of the mass uprising was almost absent in the civil administration’s response to flood in other affected districts as well. In all sorts of offices including educational institutions, there is only the circus of removing the officials who have been there until now and replacing them with new ones. The political-philosophical direction behind why the “old” ones must be removed and why it’s necessary to replace them with “new” ones has not been communicated to the field level.

As a result, these institutions have fallen into the cycle of signing attendances and various groups vying for control. Trying to avail everyday “services”, people can’t find any sign of the “Second Liberation War”.

At the end of the “war”, people are finding it hard to understand how they could be participating in the reconstruction of the country. In other words, there is no clear political and administrative “vision” that has been delivered to the districts and upazilas even after an incident as big as a mass uprising. The stimulus and promises seem to be stuck in TV screens. Unbeknownst to everyone, the seeds of hopelessness are being sowed even though the memory of the sacrifices of so many still burns freshest. But ordinary people are still not ready to lose hope. At least with Muhammad Yunus, they have a lot of trust.

Students belong on the ground, not in bureaucracy

In this tug of war between hope and despair, the students and others involved in the mass uprising could have taken the responsibility of building synergy between society and central administration. But the formation of students’ and people’s mass uprising committees in every district has not happened. They have not been assigned any specific activity relating to building the country. If the will is there, even now they can be used to accomplish a variety of nation-building activities.

On the ground, I have heard many say that the students could have solved many long-festering problems, such as illegal encroachment of rivers, without delay. By controlling traffic across the country on the first few days after August 5, students proved that they are ready to do any practical and technical task. They proved their worth again during the flood rescue and relief operations. At that time, “old society” did help them with open hands.

At the Bangladesh Agricultural University in Mymensingh, students were seen taking initiatives to produce saplings for post-flood agricultural rehabilitation. Many may remember that a similar spirit took hold in the tumultuous days of 1972-73. But the new government is failing to give this spontaneous youth force suitable tasks to keep alight the kindling of this fire. Instead of fashioning a “combined national role” for students, we have seen a handful of student leaders become advisers to the government. Perhaps a few more of them will join bureaucratic activities.

The highest achievement from all of this could be a “synergy” between the students and the people, and the old bureaucracy. But the demand of the mass uprising was not coordination with the colonial administration, or the debuts of students and new people within the bureaucracy. The demand was its complete reform. A full-body change. The consequence of the present organisational strategy is twofold. First, it’s leading to a bureaucratisation of talented student organisers as they waste their valuable time in administrative complications over appointments, transfers, suspensions, and so on. Second, watching the “coordinators” of the movement work like this could lead to pessimism particularly among the Generation Z.

Both scenarios would be extreme forms of self-sabotage. It is as though the “Spring” is being forcefully transformed into a “Winter”.

The uprising that started under the leadership of the Anti-discrimination Student Movement platform remains incomplete without the expected transformation of the state. That is why the entire leadership group of the student movement should have been on the ground for a much longer period. They should have highlighted the demands of reform from the field level. They should have compiled these demands and continuously presented them in front of the government. Only in this way could the uprising live on as a continuous process. The civil administration would not have been able to sit idle in sabotage like it is doing now.

But instead, some dangerous signs of superiority and chauvinism can be seen now. Some specific young people are being given the proprietary rights for the “mass” movement. Some are being affectionately given the title of “masterminds”. But if we removed the bubbles of individualism, we would see that the “mastermind” of the Bangla Spring is an all-encompassing desire for democracy. The students and the people turned the quota reform movement into a one-point movement a day before the “coordinators” uttered it. We must not forget that.

The movement should be made more inclusive

Considering that the July-August movement did not happen under the leadership of one person or party or coalition, it is illogical for the student body of one university to claim sole authority over the movement. In fact, this movement does not belong to a coalition of many universities either.

The descriptions of those killed and wounded in the movement make it clear that it was a movement of people of all classes and professions. In fact, it is historically inaccurate to characterise this movement as having started with the quota reform question and ended with the fleeing to India of Sheikh Hasina.

The essence of the 14-15-year-long struggle of people of many classes and professions has lent itself to the Bangla Spring. Thus, it is not just a child born to the middle class during the month of July. Without the realisation of the desires of so many people through this long period of time, this movement will not stop. In that sense, only a fair election will not fulfil the demands of the labourers killed or wounded in this movement.

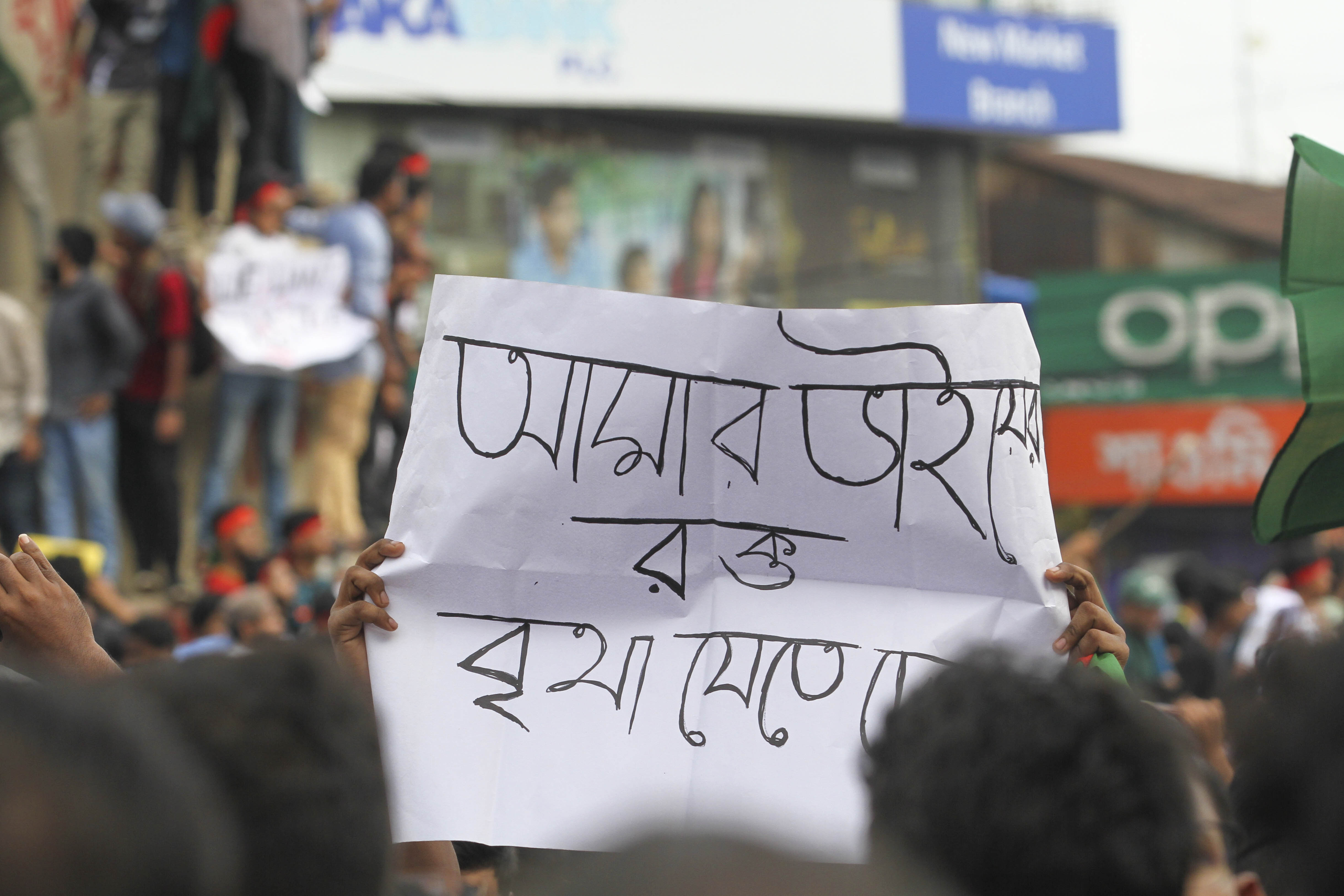

There are no universities in the spot—Dhaka's Jatrabari—where most people were killed during the movement. It is mainly an area of labourers. The bloodiest resistance during the mass uprising occurred here. These people did not sacrifice their lives on the issue of quota reform. Various longstanding crises in their day-to-day lives led them to take to the streets. They were unable to forget the feeling of insult borne out of an omnivorous culture of extortion and the denial of the right to vote in a number of elections.

So, the fact that people of these classes and professions are appearing in front of the government with their demands is not unnatural. It is all a sign of a society reborn that everyone, from labourers of pharmaceutical companies to rickshaw pullers, is engaging in processions and meetings. The incidents of beating up members of Ansar or doctors are very reactionary in nature. The central leadership of the Anti-discrimination Student Movement needs to rethink these issues.

To raise the inclusive profile of the movement, the demands of different classes and professions must be considered with importance. The organisers of the Anti-discrimination Student Movement can go to people from all walks of life and explain to them why it’s important to give room for political reforms. The powers of the movement need to be synergised with various marginal groups, instead of synergising it with the bureaucracy. Chasing away the different professional groups who are raising demands now will have a boomerang effect in the long run. Even now, the fact that the public is accepting this government as inclusive enough—despite the fact that there is no representation of workers and farmers in the adviser’s council—is because of their love for the students, and trust in some of the advisers. But nothing is permanent.

Meanwhile, the lack of participation by female students in the decision-making process of the Anti-discrimination Student Movement is becoming notable, whereas a big base of power for the July-August movement was the long processions that female students would call during days and nights. Not only on the university premises, but in districts and upazilas too, young women were in the vanguard of the movement with tremendous emotion and excitement. The traditional ideas about Bangladeshi women long held by our society have, by and large, been erased this time. Only an anti-discriminatory, democratic society can adopt the progressive elements of the recent movement. But in the field, there are some different tendencies too. One of them is to transform the mass uprising into a so-called “cultural war”. Already, Islamic parties are sitting together with a “revolutionary” goal, according to the media. Organisers of many “banned” organisations are having cases against them withdrawn, as per media reports. Many in the “intelligentsia” are raising public support to transform the current government into a “revolutionary government”. The “united power” of July 36 (August 5) is getting split into many subgroups like this. Many are trying to stuff their ideological desires into the spirit of the uprising.

But on the ground during July-August, the pictures were different. Everyone’s demand was for democracy. The anger against a massacre made this demand explosive. People stood up in front of deadly guns not because of some “revolutionary ideology”. It wasn’t the call of the intelligentsia that made them do it, it was the desire for a democratic society. It was against the limitless authoritarianism of one person. It was against unthinkable police dominance within society.

Between July 34-36 (August 3-5), Bangladesh saw the explosion of a united democratic desire among people of all classes and professions. The demand for democracy was the revolutionary desire then. Following on from that, establishing meaningful democracy is going to be the true revolutionary programme now. The intelligentsia making more “revolutionary” demands can be seen as undue pressure on the interim government.

But to fulfil the fundamental expectation of the Bangla Spring, some crucial reforms of the state’s colonial structure is a must. Among them are reforms for the local government system and many institutions like the Election Commission. To move forward with these reform programmes, it might be necessary to rewrite the constitution too. For that, experts have said that the proposed election could be organised in the form of the people’s council election of 1970. Meanwhile, the interim government needs to undertake some quick reforms, and for that, they need the political parties to participate and consent to them. Without this much-needed participation, it will be difficult to realise the goal of transformation and to make it durable. In this scenario, the centrist BNP needs to play a special role and stand with the government.

On the ground, BNP activists need to suppress their tendency to take control and occupy, and the prime responsibility of the leadership of the party has to be to help the government in their reform agenda.

BNP has a big responsibility

At this moment, BNP is definitely a major force among the political parties. They themselves have already proposed some reforms. As a result, there is little room for BNP as a power in the movement to disagree with the non-partisan students and people and the interim government. However, BNP’s reform proposals are very mild in their characteristics. A positive aspect is that Ganatantra Mancha, a major proponent of reform politics in Bangladesh, stands as an ally of BNP. If these two parties cooperate with the government that is enthusiastic about enacting reforms, there is no need to delay the elections.

If the election is left hanging for an indefinite period of time, then the development work on the ground is bound to slow down. Besides, without an elected government, there will be scant foreign investment.

From the upazilas to the national parliament, there are no public representatives at any level. On the one hand, the administration that has been a victim of partisanship is in extreme turmoil; on the other hand, the same structure has to deal with the pressure of implementing the annual development plan. The result is easy to guess. Thus, reform and elections must both be undertaken. In between all of this, those responsible for the corruption and crimes of past years must be brought to justice.

Despite credible news of the loot of thousands of crores of taka by mafias masquerading as industrialists and politicians, if they are not brought to justice and punished then the powers of the movement will have no option but to enact people’s courts in the country. The culture of corruption-disappearance-murder has put Bangladesh into an existential risk. To stop corruption on a structural level, the anti-corruption commission must be reformed according to the current political desire.

To move the reform agenda forward, news media must be rebuilt as mass media

The media world now has an enormous responsibility to understand the local nature of corruption. Revoking the Cyber Security Act and rescuing media organisations from the hands of businessmen-appointed mercenaries are the initial demands in this case. Broadcast mediums can be brought under a trust where institutions are managed in a journalism-friendly way.

Over the past years, the broadcast media has been used like tissue paper for the powerful, while hardworking journalists could not write or say much in fear of the Digital/Cyber Security Act. Cases and harassment were every-day occurrences.

The editor of the premier English newspaper of the country once told this writer about the 80 cases filed against him. How can the media contribute to building the country from this situation? But instead of any structural solutions, opportunist media “houses” of the past have suspended and appointed one or two people to resort to hide-and-seek games.

Attention also must be given towards stopping anti-Bangladesh campaigns in the outside world. An effective way of stopping this is to conduct credible investigations over the violent incidents that occurred in recent weeks and to use fact-checkers en masse. A second way is to engage the leadership of different religions and ethnicities in extensive diplomatic activities. In this, the government and the student movement must show the courage to neutralise any right-wing sabotage at the root.

Going forward, the pluralistic character of the mass uprising must be sustained throughout Bangladesh’s future.

Altaf Parvez is a researcher and writer

Back to Homepage