Hijacking History: 1971 narratives in the Awami League's reign

Priyam Paul

Every regime change in Bangladesh has been accompanied by efforts to reshape the historical narrative, particularly concerning the events of 1971. This mirrors James Baldwin's assertion that "history is not the past; it is the present. We carry our history with us." While Baldwin addressed colonial narratives about Black people, Bangladesh’s political history reveals a similar fragility, as each government selectively rewrites the past to suit its agenda, often disregarding the contributions of the original 1971 leaders. Under the prolonged rule of the Awami League, this trend intensified, with history becoming increasingly distorted under political pressure.

The narrowing of the 1971 narrative to align with the party's perspective was intended to legitimise its hold on power. Yet, this approach proved ineffective, as such narratives rarely endure beyond the regime’s tenure.

In the Indian subcontinent, the concept of 'writing history' gained significance during British colonial rule, part of an effort to reclaim a fractured national identity. Documenting history was particularly challenging in Bengal, where the tradition of maintaining chronological records was weak. Bengal’s political landscape underwent dramatic changes due to two major partitions—1905 and 1947—culminating in the creation of independent Bangladesh in 1971. Writing the history of the 1971 Liberation War, the most pivotal event in the region, remains a complex task. This war continues to shape the present, deeply influencing our understanding of the past.

Creating an objective historical account today is fraught with difficulties, as multiple actors offer conflicting interpretations, often blurring facts with personal perspectives. Memoirs, highly subjective in nature, can cause discomfort for those involved in significant events. A notable example is India Wins Freedom by Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, who left 30 pages of his memoirs unpublished for 30 years after the book’s release; these pages were only made public in 1988, after his death.

Photo: Anwar Hossain

Writing history is a daunting task, especially when it comes to the events of 1971. The process is further complicated by the need to access archives, firsthand sources, and various materials to develop a comprehensive understanding. Historian Srinath Raghavan, for instance, observed that archives in Pakistan remain tightly closed due to the controversial nature of this period in the country’s history. Similarly, Bangladesh lacks official archives from 1971, as most documents were destroyed by Pakistani forces before their surrender. Consequently, Raghavan was unable to access any archives from either Pakistan or Bangladesh—two key stakeholders in the 1971 conflict—for his book 1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh.

The formal effort to collect materials on the 1971 war effectively ceased after the publication of the 15 volumes of Swadhinota Juddher Dolilpotro. Only about three percent of the documents were published, with the rest lost due to successive relocations. These challenges underscore the immense difficulties in documenting the history of the 1971 war.

Hasan Hafizur Rahman, the editor of these volumes, noted the lack of societal support in gathering materials related to 1971, with only a few individuals offering assistance. He identified two reasons for this: first, a general lack of historical awareness, which resulted in the neglect of crucial documents; and second, a widespread suspicion that the project was government-backed, raising doubts about its integrity. Rahman emphasised that ordinary people are the true agents of change; when their desire for transformation becomes unstoppable, capable leadership naturally emerges, as was the case in Bangladesh.

Beyond the issue of archives, the memory of the 1971 war was complex and often suppressed in the years following the conflict. During the period of direct and indirect military rule from 1975 to 1990, participants in the war were hesitant to recall the events openly due to the failure of democracy, widespread disillusionment, and the unexpected rise of junta rule. Additionally, Sheikh Mujib's role was deliberately downplayed in national commemorations of the war. Despite these challenges, efforts to document the 1971 war persisted, and some notable books were published during this time.

Despite efforts to downplay Sheikh Mujib's role over two decades, he remained a central figure in discussions about the independence movement. The attempts to diminish his legacy only served to enhance his stature, resonating not only with those who experienced the war firsthand but also with a younger generation without direct memories of it. In the 2008 election, these young voters played a crucial role in the Awami League’s landslide victory, inspired by Mujib’s enduring commitment to Bangladesh’s issues and his vision of a just republic.

In 1974, Abul Fazal (1903-1983), in his seminal work Subhabuddhi, noted that even the supreme leader of the movement—later the Prime Minister of Bangladesh—had not anticipated independence until the night of March 25, 1971. Most people expected a peaceful settlement, but that night the junta launched the war. With no other choice, the resistance began, ultimately leading to Bangladesh’s independence. At the time of writing this book, Fazal was Vice Chancellor of Chittagong University, and Sheikh Mujib held him in high regard as a distinguished scholar and intellectual.

Regarding the preparedness for war, renowned writer Mahboobul Alam (1898-1981) assessed the Awami League’s strategy during the non-cooperation movement leading up to March 1971 in his three-volume work Muktijuddher Itibritto (1976). He observed that while the Awami League applied maximum pressure on the Pakistani junta through its movement, its actual preparations for war were minimal. As a result, the war encountered significant difficulties from the outset due to a lack of necessary groundwork.

Kamruddin Ahmad (1912-1982), a noted political observer and writer, in his book Swadhin Banglar Abhyuday Ebong Atapar (1982), supported Mujib's decision on March 7th not to declare independence, despite pressure from youth leaders. These leaders believed that the police, EPR, and East Bengal Regiment were ready to declare independence and could resist the forces of East Pakistan. However, Mujib, aware of Pakistan’s superior firepower—one of the highest in Asia—remained cautious, a decision that proved wise by the morning of March 26, 1971.

Ahmad also noted that in 1970, prominent figures like Maulana Bhasani and Ataur Rahman Khan had repeatedly called for independence, but these proclamations had little effect. In contrast, Sheikh Mujib focused on the election, avoiding any actions that might endanger it. The situation was so volatile that many leaders struggled to recognise each other, each believing themselves to be the true leader of the people. Yet, despite these challenging circumstances, Sheikh Mujib navigated the situation without error.

Sheikh Mujib's residence, later turned into a museum, on Dhanmondi 32 was vandalised and set on fire by a mob on August 5.

Kamruddin Ahmad raises an important methodological question about documenting the history of 1971, highlighting that it cannot rely solely on the recollections of those directly involved. Even 200 years from now, writing this history would remain difficult due to the absence of a comprehensive archive. Therefore, there is no simple or straightforward way to document the 1971 War.

A key aspect of historical inquiry into the 1971 war is whether there was a concrete plan to wage war against the Pakistani invaders. The Awami League, however, has often appeared uncomfortable addressing this issue, frequently questioning the motives behind such inquiries and implying that they stem from anti-liberation forces.

It’s also essential to consider the challenges faced by Sheikh Mujib and the Awami League during the 1971 war, as they were more accustomed to conventional democratic politics and were gradually forced into a full-scale conflict with Pakistan. Opinions on this issue vary among war participants, and historians inevitably interpret events through different lenses. Interestingly, discussions about 1971 were more open during the first two decades after independence than they have been in recent years under Awami League rule.

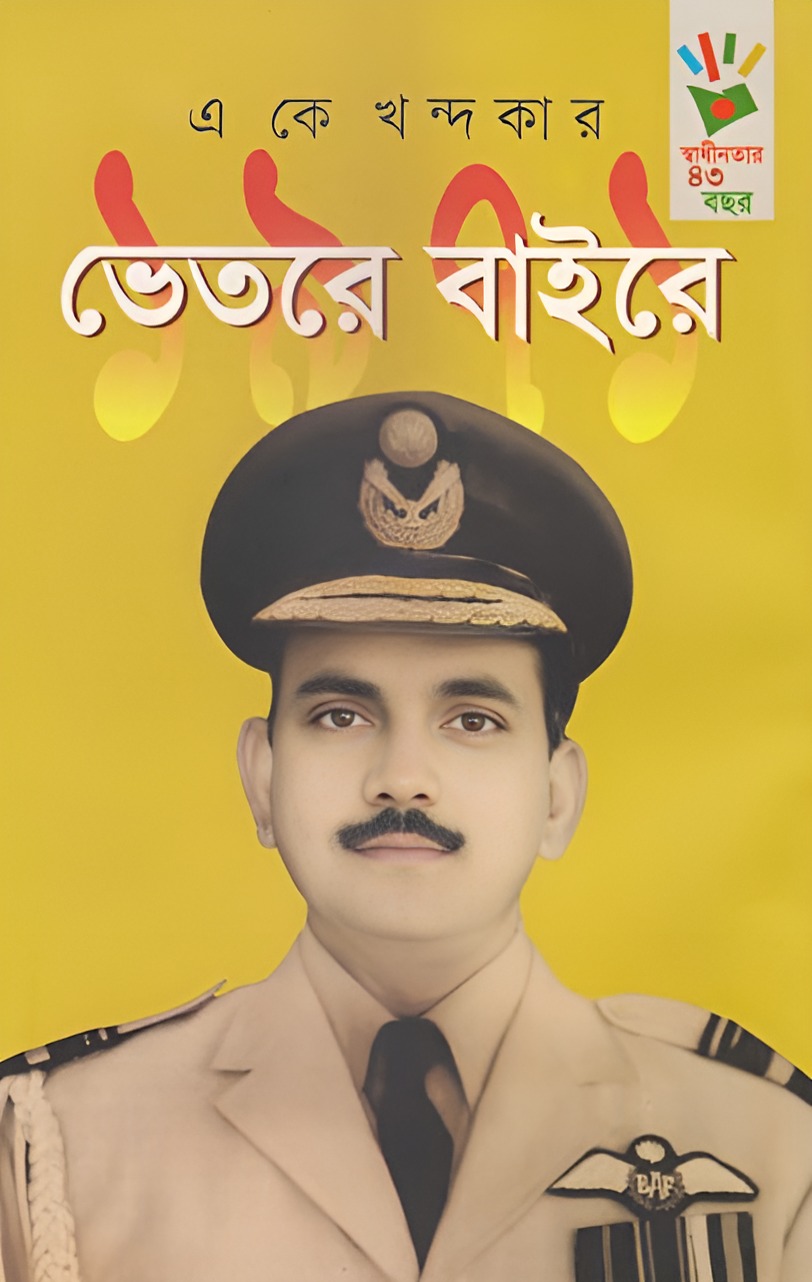

Notably, figures like Abul Fazal, Mahboobul Alam, and Kamruddin Ahmad were able to question the dynamics of the 1971 war more freely than A.K. Khandaker did in 2014. Yet, Khandaker himself had expressed similar views earlier in his interview for Swadhinota Juddher Dolilpotro, which did not spark the same controversy it did in 2014.

It’s also worth acknowledging some significant efforts made during the past Awami League rule. Sheikh Mujib's unpublished manuscripts were released with careful editing and translated into multiple languages. These manuscripts have become invaluable, offering deep insights into Mujib's life and era, as well as the social and political history of Bengal from the perspective of a prominent Bengali Muslim leader.

In addition, a 14-volume work titled Secret Documents of Intelligence Branch—which compiles files maintained by Pakistan's Intelligence Branch—was published. Looking ahead, there is a strong need to expand this effort by declassifying and publishing documents related to other significant political leaders of that era. This would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the Pakistani period, provided that rigorous academic standards are maintained.

Some issues, though not directly related to the writing of the history of the 1971 war, were closely tied to individual roles during that time. Actions taken by the state apparatus during the last Awami League regime created an atmosphere of bitterness and fear, discouraging open discussions and writings about 1971.

In August 2016, the cabinet approved a draft law that included a provision for life imprisonment and a Tk 1 crore fine for dishonouring the Liberation War or Father of the Nation, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The proposed Digital Security Act of 2016 also stipulated that anyone using digital devices to spread propaganda against the Liberation War or Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman would face the same penalties as those distorting court-established facts about the Liberation War. Alarmingly, the process of shaping history extended into the courtroom.

In December 2019, the Liberation War Affairs Ministry published a controversial list of individuals allegedly collaborating with the Pakistani occupation forces during the 1971 war. The list included several freedom fighters and pro-liberation figures, which was seen as highly offensive, particularly in cases like that of Dr. Manisha Chakraborty, a prominent leader from Basad’s Barisal district unit. Her grandfather, Sudhir Kumar Chakraborty, had been killed by the Pakistani army, her father, Tapan Kumar Chakraborty, was a freedom fighter, yet her grandmother, Usha Rani Chakraborty, was listed as a collaborator. This incident not only exposed the ministry’s inefficiency but also raised suspicions of political vendetta, given that Manisha had contested against the ruling party candidate in the Barisal City Corporation election, losing amid allegations of massive electoral fraud.

On February 21, 2021, the Jatiyo Muktijoddha Council, a government body responsible for maintaining records of freedom fighters from 1971, decided to revoke the gallantry title ‘Bir Uttam’ awarded to former president Ziaur Rahman, founder of the BNP, along with four individuals involved in the killing of Sheikh Mujib and his family. Although Ziaur Rahman was not implicated in the assassination, this move was seen as political vengeance. Such actions, though seemingly unrelated to the history of 1971, severely undermined the public’s shared connection to the events of that year.

In the same year, numerous government events were held to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Liberation War. But did these truly honour the contributions of Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani or Tajuddin Ahmad, two pivotal figures in the long struggle against Pakistani rule? Sadly, their roles received little recognition in these state-sponsored observances, which were largely uninspiring and failed to meaningfully engage the public in celebrating this monumental occasion on a national scale.

The anti-colonial Indian independence movement successfully established a widely accepted historical narrative that continues to command respect for its key figures. In contrast, recent attempts by the ruling party in India to rewrite history by glorifying a Hindu past have yet to significantly reshape the broader understanding of the national movement. The history of India’s independence has been written from diverse perspectives—regional, micro, women’s, subaltern, and Dalit—resulting in a more inclusive narrative. Unfortunately, the history of Bangladesh’s national movement has been narrowed by party-driven narratives, reducing it to the celebration of a single figure as a 'Superman' for all seasons.

Didn’t the prolonged rule of the Awami League aim to elevate one great man, thereby creating a barren narrative of uniformity about the 1971 war? The practice of using wisdom and remaining faithful to the truth is vital for documenting the history of the Liberation War, even if that truth is melancholic and uncomfortable. Sadly, these qualities were notably absent in the Awami League’s partisan narrative of 1971.

The most heinous crime, however, was the burning of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib’s historic residence at Dhanmondi 32 on August 5, 2024—a site central to many crucial events during 1971. Though this act of destruction will not tarnish Mujib’s legacy, it severely damaged Bangladesh’s international image, casting the nation as barbaric. It also reflects a troubling mindset, marked by a lack of historical awareness and respect for our heritage.

Priyam Paul is a researcher and journalist at The Daily Star.

Back to Homepage